There is no need for us to worry about Tiatr. The now century old tradition is

alive and kicking and shows no sign of slowing down. If there is one thing that

needs to be addressed, however, it is the practice of shaming that Tiatr is

often subject to. Too often, Tiatr is compared to Indian drama forms that were

formed in the course of the anti-imperial nationalist movement in British

India. These drama forms took a good amount of inspiration from Western

European traditions and sought to articulate similar plays in vernacular

mediums. A part of this process was to also ‘purify’ vernacular dramatic

traditions. Thus, art forms like Bhavai

in Gujarat, Tamasha in Maharashtra

were sought to be made ‘respectable’. What is often not discussed, however, is

that both the nationalist movement as well as these attempts in the theatrical

world were often made by upper-caste persons. Their attempt was to assert

upper-caste control over the art form and determine what was acceptable and

what not. In this process, the subaltern caste groups who had birthed these art

forms were excluded on the basis of their lack of aesthetic refinement and

‘vulgarity’. Where these subaltern groups did not submit meekly to upper-caste

assertions, these performers were shamed most vigorously and systematically.

This is also true of Tiatr. Indeed, a critical reading of the history of Tiatr

would suggest that the form was born from the attempt to clean up the Khell that were being performed by

migrant Goan groups in Bombay. Fortunately, however, once the form of the Tiatr

was set up, the subaltern Goan groups reasserted their control over the art

form. This reassertion is at the root of the constant criticism that Tiatr

draws; that it is lacking in standard.

There is no need for us to worry about Tiatr. The now century old tradition is

alive and kicking and shows no sign of slowing down. If there is one thing that

needs to be addressed, however, it is the practice of shaming that Tiatr is

often subject to. Too often, Tiatr is compared to Indian drama forms that were

formed in the course of the anti-imperial nationalist movement in British

India. These drama forms took a good amount of inspiration from Western

European traditions and sought to articulate similar plays in vernacular

mediums. A part of this process was to also ‘purify’ vernacular dramatic

traditions. Thus, art forms like Bhavai

in Gujarat, Tamasha in Maharashtra

were sought to be made ‘respectable’. What is often not discussed, however, is

that both the nationalist movement as well as these attempts in the theatrical

world were often made by upper-caste persons. Their attempt was to assert

upper-caste control over the art form and determine what was acceptable and

what not. In this process, the subaltern caste groups who had birthed these art

forms were excluded on the basis of their lack of aesthetic refinement and

‘vulgarity’. Where these subaltern groups did not submit meekly to upper-caste

assertions, these performers were shamed most vigorously and systematically.

This is also true of Tiatr. Indeed, a critical reading of the history of Tiatr

would suggest that the form was born from the attempt to clean up the Khell that were being performed by

migrant Goan groups in Bombay. Fortunately, however, once the form of the Tiatr

was set up, the subaltern Goan groups reasserted their control over the art

form. This reassertion is at the root of the constant criticism that Tiatr

draws; that it is lacking in standard. In recent times

it has become somewhat commonsensical to lay the blame for this shaming at the

doorstep of the proponents of Nagari Konkani. While this may be politically

expedient, this is not the whole truth. Tiatr is often shamed by its own

proponents, largely because they have internalised the criticisms levelled by

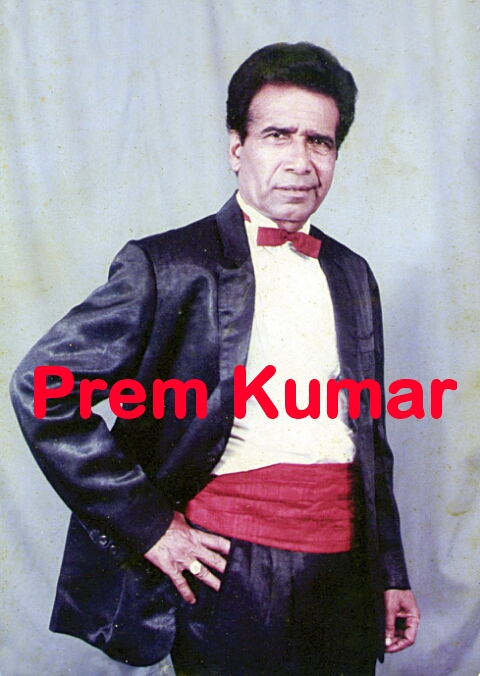

persons from the broader Indian nationalist theatrical traditions. Take, for

instance, an anecdote about the tiatrist Prem Kumar that is often recounted by

Tiatr activists. The story goes that Prem Kumar once took Vasant Joglekar, a

significant name from the world of Marathi theatre to watch a tiatr at P.T.

Bhangwadi. The tiatr apparently had a scene where the home of a landlord was

shown against the backdrop of a jungle. Joglekar must have responded derisively

to this juxtaposition of a landlord’s home against a jungle because Prem Kumar

is reported to have been ‘put to shame’ by Joglekar’s reaction which initiated

Prem Kumar’s lifelong quest to ‘uplift’ the Konkani stage.

In recent times

it has become somewhat commonsensical to lay the blame for this shaming at the

doorstep of the proponents of Nagari Konkani. While this may be politically

expedient, this is not the whole truth. Tiatr is often shamed by its own

proponents, largely because they have internalised the criticisms levelled by

persons from the broader Indian nationalist theatrical traditions. Take, for

instance, an anecdote about the tiatrist Prem Kumar that is often recounted by

Tiatr activists. The story goes that Prem Kumar once took Vasant Joglekar, a

significant name from the world of Marathi theatre to watch a tiatr at P.T.

Bhangwadi. The tiatr apparently had a scene where the home of a landlord was

shown against the backdrop of a jungle. Joglekar must have responded derisively

to this juxtaposition of a landlord’s home against a jungle because Prem Kumar

is reported to have been ‘put to shame’ by Joglekar’s reaction which initiated

Prem Kumar’s lifelong quest to ‘uplift’ the Konkani stage.

What is tragic

in this scenario is that Joglekar’s sensibilities were seen as beyond question,

rather than limited by his own agendas and cultural background. Unfortunately

confined by brahmanical sensibilities and nationalist anxieties perhaps he

missed crucial clues in the backdrop?

I recently had

the opportunity to view Mario Meneze’s Suicide

at a Tiatr festival in Velsão-Pale and was struck by the backdrops that were

used in the course of the Tiatr. The curtain that was used when the Cantarist

came on was of a scene of the city of London with the famous Tower Bridge as

the centre. Curiously, it was marked by a very Goan balustrade that framed the

lower length of the curtain. The second interesting background, used to

indicate the environment outside of the house of the protagonist was of the

Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. Now one could, like Tendulkar scoff at these

backdrops. For example, why London? And if London, why that Goan balustrade in

the scene? Can they not be realistic in their depiction? Worse still, Menezes

is writing a play about Goa, and allows for a scene from Berlin to depict the

Goan village space? Does he have no sense of geography? Alternatively, one

could put aside one’s prejudices, and look at these backdrops anew and realise

that they are testament to the cosmopolitan world that the Goan lives in.

I recently had

the opportunity to view Mario Meneze’s Suicide

at a Tiatr festival in Velsão-Pale and was struck by the backdrops that were

used in the course of the Tiatr. The curtain that was used when the Cantarist

came on was of a scene of the city of London with the famous Tower Bridge as

the centre. Curiously, it was marked by a very Goan balustrade that framed the

lower length of the curtain. The second interesting background, used to

indicate the environment outside of the house of the protagonist was of the

Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. Now one could, like Tendulkar scoff at these

backdrops. For example, why London? And if London, why that Goan balustrade in

the scene? Can they not be realistic in their depiction? Worse still, Menezes

is writing a play about Goa, and allows for a scene from Berlin to depict the

Goan village space? Does he have no sense of geography? Alternatively, one

could put aside one’s prejudices, and look at these backdrops anew and realise

that they are testament to the cosmopolitan world that the Goan lives in.

Realism in

theatre is highly over-rated. Theatre is not real life; it is a representation

of reality, and as such, relies profoundly on symbols. I would like to read the

curtains used at the staging of Suicide

as the example of the sophisticated use of symbols. The Goan balustrade running

through the bottom of that first curtain was not a mistake. On the contrary it

symbolised the Goan’s view on the world. For close to two centuries now Goans

have been migrant workers going beyond the subcontinent to the world at large.

Indeed, so wide is the diaspora that London now stands in for what Bombay

represented earlier; a second home for Goans. In such a scenario, that

balustrade symbolises Goan ownership of that London vista. It tells to the

audience that the migrant Goan may be out of Goa, working in London, but she or

he is still firmly rooted within Goa. They inhabit both worlds.

Similarly the

Brandenburg gate. To read the backdrop literally would be to miss the wider

point that theatre is capable of making. Given that this curtain was used to

denote the outside of the home, it made a very nuanced point. Berlin is indeed

a part of the Goan outside. But once again, it is an outside that is still

sensible to a Goan audience many of whom have friends and family who are widely

travelled.

(A version of this post was first published in the O Heraldo dated 23 May 2014)