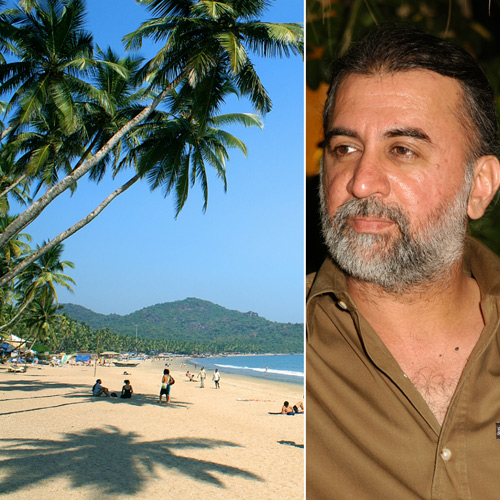

Much opinion has already been generated of Tarun Tejpal’s alleged attempt to rape his junior colleague, and no doubt much more will be written. In addition to these diverse positions, it appears that it may be possible to also use this incident to gauge the nature of the Indian nation-state and its relationship with the peoples and territories that constitute its national peripheries.

This gauging can begin

from what many commentators have dismissed as a “passing” statement from Tejpal

himself. In 2011, on the eve of ThinkFest’s first edition, Tejpal had suggested

to early birds at the event's plush venue: "Now you are in Goa, drink as

much as you want, eat... sleep with whoever you think of, but get ready to

arrive early at the event as we have a packed house."

This gauging can begin

from what many commentators have dismissed as a “passing” statement from Tejpal

himself. In 2011, on the eve of ThinkFest’s first edition, Tejpal had suggested

to early birds at the event's plush venue: "Now you are in Goa, drink as

much as you want, eat... sleep with whoever you think of, but get ready to

arrive early at the event as we have a packed house."

Then, as much as today,

the intense responses to this statement from Goans were seen by Indian

commentators as akin to making a mountain of a mole hill. To these media pundits

Tejpal’s statement was merely an off-the-cuff remark that should not be taken

too seriously. Indeed, some have gone as far as to say that it should still

not be taken too seriously, and in any case does not compare in severity with

the crime that Tejpal has been accused of.

This article does not

attempt to equate these two incidents involving Tejpal, but it would like to

suggest that the relationship between them is much deeper than these national commentators

would allow for.

To begin with, the very

fact that there is a disagreement over how to view this statement suggests the

widely divergent perspectives of Goans and the Indian elites who frame national

news. This dismissal of the Goan response also manifests another way in which

‘mainstream’ India sees Goans as simple, emotional and not given to balanced

thought. Further, it demonstrates how local contexts are not given enough

importance in the mainstream’s

evaluation of things.

If there was a reason why

many Goans reacted at all it is because of the systemic manner in which their

state has been treated as a pleasure periphery of the nation. California-based

scholar Raghuraman Trichur has proposed that it is through tourism, rather than

politics, that Goa has been incorporated into the Indian imagination. This small state on the

country's Western coast is

indeed seen as part of its pleasure periphery , India’s very own piece of

locally available Europe.

The

roots of this image of Goa can

be traced back to colonial times. One of the primary sentiments motivating the British

Indian native elites’ demand for freedom was their failure to upgrade their

status from imperial subjects to that of imperial citizens. The latter would

have allowed them parity with the metropolitan British not only in British

India, but across the breadth of the Empire where Indians were a critical part

of the imperial machinery. At the root of their freedom struggle, therefore,

was the pique at not being considered equal to whites.

Procuring Goa subsequent

to Indian independence, and framing it as a piece of Europe, provided added

consolation. This was where British Indians could enjoy the privileges of

Europe as first class citizens and masters. The

active participation of the Goan state and the tourism industry only aided in

cementing this notion.

In the process, Goa has frequently been the subject of marketing campaigns suggesting it is on holiday 365 days a year, promising nothing short of surf,

sand, and sex.

In many ways Tejpal’s

personal association with Goa demonstrates all that is wrong with India's

relationship with this state.

Tejpal's 2011 statement

clearly demonstrates what he thought of Goa: a place where rules don't matter

and one can behave as one wishes. It would not be amiss to suggest that there

is a hint of that infamous American idiom, “What happens in Vegas stays in

Vegas”. People who live in Goa will testify that all too often, the behaviour

of tourists adheres to a similar belief. However,

it is evident from the explosion of responses to the charge against Tejpal that

this is not always true, that what happens in Goa, does not always stay in Goa.

And as if to prove he is not an exception but

the rule, no sooner did the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) begin

in Goa shortly after ThinkFest, that a festival official was charged with

sexual harassment.

In this particular incident, the official was accused by a female subordinate

of suggesting that they could have drinks and then engage in “all other things

(aur sab kuch)”. Where Indian culture is actively defined as a non-alcoholic

one, arrival in Goa, with its more balanced response to the public and

convivial consumption of alcohol, is seen as opening the doors for licence and

licentiousness.

Another way in which

Tejpal typifies the national elite’s colonial relationship with Goa is his

ownership of a property in the village of Moira.

Those familiar with the

Indian upper-middle classes will know that a second home in Goa is de rigueur. Ideally, it must be a

building that goes under the erroneous name of a “Portuguese house”. That these

properties are unlike anything in Portugal is hardly the point. Calling them

Portuguese homes denies a unique Goan identity, and allows the Indian elites to

produce the myth that they are in an Indian piece of Europe.

One way in which

colonialism operates is to deny the local identity and assert only the

national, while simultaneously exploiting the local for the benefits that it

offers the colons. Possession of such

homes mirrors the holiday-making of contemporary Northern Europeans, but also

of English grandees from the nineteenth century. These grandees would own

properties in southern Europe, host their friends , and use these locations to

engage in romantic interludes and sexual practices that would have invited

disapproval in their own countries.

One way in which

colonialism operates is to deny the local identity and assert only the

national, while simultaneously exploiting the local for the benefits that it

offers the colons. Possession of such

homes mirrors the holiday-making of contemporary Northern Europeans, but also

of English grandees from the nineteenth century. These grandees would own

properties in southern Europe, host their friends , and use these locations to

engage in romantic interludes and sexual practices that would have invited

disapproval in their own countries.

Tejpal’s house in Goa

fits neatly into this model, given that it is also rented out as a Portuguese

villa when the Tejpals are away. It is not ironic that while this property is

marketed as one offering a taste of the openness that marks Goan society, locals have criticised the Tejpals

for erecting a 2-metre high boundary wall.

Once again, Tejpal's is

not the only infraction; numerous similar properties violate the regulation

capping the height of a boundary wall at 1.5 metres. What is striking is his

response to a public statement that challenged

his purported disregard of building regulations. After dismissing all

the allegations as false, in a tone reminiscent of the white man’s burden,

Tejpal suggested he was doing Goa a favour since “the house we bought was an old ruin

in an inner village”.

The final nail in the

coffin is how another one of Tejpal’s babies, ThinkFest, engages with Goa. This

year, a number of local activists protested the event, drawing attention to

the fact that the venue violated CRZ regulations, and that the event was

supported by corporations that not only made their profits from mining but were

known to have perpetrated significant human rights violations against indigenous

groups that opposed them.

More horrifying are

suggestions that the Tehelka editors procured financial support for ThinkFest

by suppressing investigative reports on mining scams in Goa that would have

implicated government officials. Most disturbing is that even as ThinkFest is

held in Goa amidst dubious circumstances, it hardly engages with the locals.

The passes for the event are priced beyond the reach of average middle class

Goans, let alone those of lesser economic means. Once again, Goa is merely a

location to be exploited for its

scenic beauty, another spot that marks the exotic social calendar of the

jet-set.

Debates in social media

have charged that this focus on Goa as a space is meant to effectively turn the

focus away from women and the alleged crime. A riposte to this would be to

point out that rape, in addition to being about the violation of women’s

bodies, is also about relations of power.

To limit the discussion

that flows from Tejpal’s alleged actions to rape and women alone is to fall

back into the trap of thinking along the agendas set by the national elite. As

pointed out above, this is an elite that would prefer that we forget the

particular and focus on apparently universal categories.

Looking at gender between

the binaries of male and female alone is the very strategy through which the

secular-liberal discourse ensures that the specificities of caste are

forgotten, such that the rape of Dalit women and men by upper caste groups are

often neatly left outside of national debates.

Focusing on location, as

this article has attempted to do, seeks to situate the various kinds of locales

within which women (and men) may be placed in a position where they are unable

to refuse the sexual advances of those above them in social-political

hierarchies. For example, does reducing the question in the present debate to

just the aggrieved woman alone not deem irrelevant the harassment that all

women in Goa, whether local or visiting, must face as a result of its

construction as a lotus-eater’s paradise?

A focus on locale also

allows us to see why certain kinds of behaviour are made to seem more

acceptable in some locations, like hotels or tourist destinations, and not

others. It could be argued then, that the scene for

the crime that Tejpal has allegedly committed was set on the day his statement

– which painted Goa as a place for sexual excess – was condoned by the national

press.

Furthermore, Tejpal’s

initial response to the charge, where he smugly cast on himself the role of

judge, can be read as an extension of the egotistical way in which the elite

see themselves as entitled to bend regulations to their own advantage. The

licence to bend rules seems to operate especially when these elites can justify

their overall interventions in society as being in the public or national

interest.

Furthermore, Tejpal’s

initial response to the charge, where he smugly cast on himself the role of

judge, can be read as an extension of the egotistical way in which the elite

see themselves as entitled to bend regulations to their own advantage. The

licence to bend rules seems to operate especially when these elites can justify

their overall interventions in society as being in the public or national

interest.

(A version of this post was first published online at DNAIndia.com on 4 Dec 2013)