It was with anger and disbelief

that I read Deepti Kapoor’s recent article in The Guardian titled “An idyll no more: why I’m leaving Goa”. While

there is no denying that Goa is in fact facing a looming ecological and

political crisis, what is galling is that Kapoor does not acknowledge her own

role in the mess that Goans find themselves in. Kapoor is silent about the

privilege that she enjoys – the privilege of the (largely North) Indian elites,

who dominated British India, led the anti-colonial nationalist movement, and

who now operate as the embodiment of colonial power in places like Goa. This is

precisely the relationship that is to blame for the many ills that Kapoor

documents, and that allows Kapoor to escape Goa with relatively no loss, while

Goans are left not only with a ruined ecology and social fabric but a

continuing brutal colonial relationship with India.

It was with anger and disbelief

that I read Deepti Kapoor’s recent article in The Guardian titled “An idyll no more: why I’m leaving Goa”. While

there is no denying that Goa is in fact facing a looming ecological and

political crisis, what is galling is that Kapoor does not acknowledge her own

role in the mess that Goans find themselves in. Kapoor is silent about the

privilege that she enjoys – the privilege of the (largely North) Indian elites,

who dominated British India, led the anti-colonial nationalist movement, and

who now operate as the embodiment of colonial power in places like Goa. This is

precisely the relationship that is to blame for the many ills that Kapoor

documents, and that allows Kapoor to escape Goa with relatively no loss, while

Goans are left not only with a ruined ecology and social fabric but a

continuing brutal colonial relationship with India.

The relationship of the Indian

elites to Goa is by no means innocent. For that matter, neither is the

relationship of India to Goa. Rather, these relationships are built on the

willful ignoring of history, to enable Indians to create Goa and Goans not only

as property of the Indian empire but as a pleasure park where they can imagine

themselves to be in their own little part of Europe. Take, for example, the way

in which Kapoor chooses to label older houses in Goa “Portuguese villas”

despite the fact that many Goans, including scholars, have pointed out that there

is nothing Portuguese to these homes. Except for the fact that they were

built by Goans, who were Portuguese citizens at the time, these were, and are,

Goan homes. The reason for this stubborn insistence is linked to the fact that

these houses are in high demand by the Indian elites who choose to own second

homes in Goa. It is precisely in calling the built forms “Portuguese” that Goa

and Goans are transformed into props that allow for the territory to be read as

Europe in South Asia, as a

seaside Riviera where Indian elites can play out their European fantasies.

This colonial relationship, it

should be pointed out, is not unique to the relationship between Goa and India.

In fact, it follows a longer colonial relationship enjoyed by the Northern

European, and principally British elites, with the European South – namely,

Italy, Spain, and Portugal. It was to these historically Catholic locations

that the largely Protestant elites of the North fled to enjoy not just the sun

but the pleasures of the flesh. The European South, and by extension the

overseas colonies of these countries, were marked out as spaces for frolic and

relaxation, and fabulous lifestyles afforded as a result of the poorer

economies of the host locations. Additionally, these locations were identified

as places for inspiration for artistes and writers. In post-colonial times, the

elite British Indian has actively taken on the gaze and privilege of the

British overlord, and looks at Goa precisely through the lenses that the

British used to view the European South. No wonder then that Kapoor, author of the

novel A Bad Character (2014), also

chose Goa as a place for future writing projects.

The continuation of this imperial

gaze is also deeply rooted in colonial politics. As Sukanya Banerjee

demonstrates in her book Becoming

Imperial Citizens: Indians in the Late-Victorian Empire (2010), the end of

empire and the creation of an independent nation-state was not the goal

envisaged by early Indian nationalists. On the contrary, South Asian dominant

caste elites were stakeholders in the empire rather than its opponents. Given

this proximity to the imperial project, what they deeply desired was the status

of Imperial British citizen and equality with the British overlord. Banerjee

also demonstrates the way that Gandhi himself was invested in the pursuit of

this status. The figure of Gandhi is critical here, because it was he who effectively

created a mass movement by recruiting subaltern groups to make what had earlier

been a largely elitist cause. This mass recruitment was necessary for the

elites to be taken seriously by the British Crown. The Crown was convinced that

while the Indians merited the status of subjects, they could not be imperial

citizens and thereby claim equality with the British. The rallying of the

masses forced a change in the nature of the movement to assume the character of

a nationalist anti-colonial project. Independence was now the only answer.

Thus, the objective of the

nationalist elites was, rather, parity with the British and participation in

the imperial project. The continued desire for imperial prominence that

motivated these caste elites ensured a number of features that have marked

post-colonial India. By exerting various pressures on the princely states and

acquiring, forcefully if necessary, the territories of other colonial powers,

the nationalist elites put together an Indian empire that even the British Raj

had not managed to. This new post-colonial empire was held in place by retaining

most of the colonial laws, and an imperial perspective guided the relationship

with the territories and peoples that were assimilated into post-colonial

India. Thus, along with Goan houses being labeled “Portuguese”, Goans have been

marked out as fun-loving, relaxed, and laid back, just as the southern

Europeans and Latins. Further, just as the British elites travelled to the

European South for sensorial excess, so too has Goa been marked out as a place

for excess. Note that Kapoor’s narrative suggests that her brother had his mind

blown – normally a reference to the effect of psychotropic drugs – when he saw

his first nudist in Goa. The Kapoor family’s relationship with Goa seems to be

marked by an excess that is unavailable in India. As R. Benedito Ferrão points

out, Kapoor suggests her own sensorial relationship with Goa through the

excessive exclamation marks that she uses when listing the things that brought

her to Goa: “The beaches! The restaurants! The music, and the people!” Further,

as if to prove the point of a continuity between the imperial British and the

contemporary imperial Indian elite, Kapoor states that she has decided “to look

toward Europe or Latin America” in her search for a new place to live. It

should be obvious that Latin America is placed along the same continuum as Goa

in terms of being the place of Iberian influenced tropical languor and excess. Therefore,

Kapoor will merely shift from Goa to another location that offers a similar

southern European backdrop for the party.

Interestingly, the insistence of

Indians, such as Kapoor, on labeling the built landscape in Goa as different

from India reveals a disinclination to be attentive to the historical and legal

differences of this former Portuguese territory. Unlike the legal scenario that

unfolded in British India, Goans were constitutionally recognized as Portuguese

citizens as far back as the early 1800s. This resulted in a restricted segment

of the population being entitled to vote in parliamentary elections. And vote

they did. Goan elites regularly sent voluble representatives to Lisbon, who

established the legal and social parity of Goans with metropolitan Portuguese. This

situation was temporarily suspended in the years when Goa, like the rest of

Portugal, suffered an authoritarian regime from the 1930s until 1974. It was in

this situation that India sent troops in to militarily wrest Goa from the

Portuguese. Rather than engage with the political agency that was being

expressed within and outside of the territory, India simply asserted

sovereignty over the territory and extended citizenship to persons residing in the

territory. Given the right of colonized peoples to self-determination, this was

an act for which there was no legal precedent, but was based on the assertion

of a dubious argument of cultural homogeneity.

Interestingly, the insistence of

Indians, such as Kapoor, on labeling the built landscape in Goa as different

from India reveals a disinclination to be attentive to the historical and legal

differences of this former Portuguese territory. Unlike the legal scenario that

unfolded in British India, Goans were constitutionally recognized as Portuguese

citizens as far back as the early 1800s. This resulted in a restricted segment

of the population being entitled to vote in parliamentary elections. And vote

they did. Goan elites regularly sent voluble representatives to Lisbon, who

established the legal and social parity of Goans with metropolitan Portuguese. This

situation was temporarily suspended in the years when Goa, like the rest of

Portugal, suffered an authoritarian regime from the 1930s until 1974. It was in

this situation that India sent troops in to militarily wrest Goa from the

Portuguese. Rather than engage with the political agency that was being

expressed within and outside of the territory, India simply asserted

sovereignty over the territory and extended citizenship to persons residing in the

territory. Given the right of colonized peoples to self-determination, this was

an act for which there was no legal precedent, but was based on the assertion

of a dubious argument of cultural homogeneity.

With the normalization of

relations between Portugal and India in 1975, Portugal recognized the

continuing right of citizenship of residents of its former territories in

India. As consciousness of this continuing right percolates through Portuguese

Indian society, many have chosen to access and assert this right. The Indian

state, and consequently most Indians, however, fail to see this as a resumption

of an existing right. They see it instead, as the acquisition of dual

citizenship, which some argue is prohibited by the Indian legal system. This

places Portuguese Indians – in this case, Goans – in an awkward situation,

where they have to give up political engagement with Goa, and a host of other

rights, if they choose to assert their right to Portuguese citizenship. Like

most Indians, Kapoor seems to fail to recognize this complexity and naively

suggests that Goans are leaving, or, as she puts it, “looking elsewhere”. As I articulated

in an essay some time ago, Goans are not leaving; they are merely employing

one more way to maintain their historical connections and pursue livelihood

options. It is only in the face of an Indian state that refuses to recognize

the complexity of Portuguese Indian history, and prevents this movement, that

Goans are, in fact, being forced to

leave.

At the end of the day, it is the

refusal to recognize this most basic of rights, that of citizenship

pre-existing the Indian takeover of Goa that complicates the relationship of

India, and Indians, with Goa, and Goans. The refusal to recognize a

pre-existing constitutional right of citizenship transforms the Indian presence

in Goa into one of occupation and not post-colonial liberation.

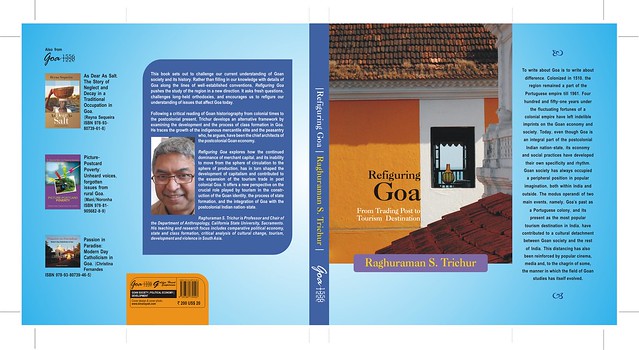

The colonial nature of India’s

presence in Goa is perhaps best captured in the way the territory has been

actively converted into India’s pleasure periphery. In his book, Refiguring Goa (2015), Raghuraman S. Trichur

points out that “it was only after the state sponsored development of tourism

in the 1980s (more than two decades after Goa's liberation/occupation in 1961),

was Goa effectively integrated into the Indian nation-state” (p. 13). This is

to say that the integration of this former Portuguese territory, which ought to

have been given the right to self-determination, was ensured through the

process of articulating Goa’s “otherness” or cultural distancing, as evidenced

by the social practices and performances that constitute the tourism

destination in Goa. Thus, Trichur argues, Goa’s emergence as a tourism

destination is more than the fortuitous agent of economic growth: “it is also an

arena, a discursive frame where the Indian State intersects with Goan society”

(p. 16). Tourism, then, is precisely the way through which Indian colonialism

is exercised in Goa. Indeed, the usage of “Portuguese” houses, in reference to

the homes of Goans, suggests homes not continually inhabited by Goans but open

for occupation by the “helpful”

outsiders that come to renew Goan life.

While Kapoor correctly lists the

many problems that are cropping up in Goa as a result of a tourist industry

gone wild, she seems to place the responsibility for the looming ecological and

social disaster primarily in Goan hands. One reads in Kapoor’s narrative the

usual suggestion that it is the greedy Goans who are selling agricultural land

and pulling down ancestral homes, and that the local government has no vision.

What escapes her is that Goans are all too often subject to forces not within their

control. Goans are trapped in an economy that, rather than working on producing

more varied opportunities for the locals, has for decades now relied

exclusively on tapping the extractive industries of either tourism or mining,

or on overseas remittances. While the tourist economy has produced huge profits

for some, incomes have not risen to keep pace with the increased cost of

living. In such a context, there are two options that will assure people

without the material resources or skill sets to fuel social mobility of persons

who cannot achieve betterment in Goa. The first is the sale of land to persons

in search of the fabled Goan lifestyle. The second is migration in search of

gainful and respectable employment. The irony is that the critique of the Portuguese

presence in Goa was that they failed to develop a viable economy, which

required people to migrate to earn a living that would assure them and their

families of a higher standard of living. Indeed, for the vast majority of the

population life under Portuguese rule was experienced more as life under

landlord rule. And this Goan lifestyle was no idyll. It was only through

migration that they could economically emancipate themselves. It was only with

the economic liberation possible through migration that Goa, now a place to

return for the summers, was constructed as an idyll. As it turns out, the

transition to Indian rule has not changed much, as many Goans are still forced to migrate.

While Kapoor correctly lists the

many problems that are cropping up in Goa as a result of a tourist industry

gone wild, she seems to place the responsibility for the looming ecological and

social disaster primarily in Goan hands. One reads in Kapoor’s narrative the

usual suggestion that it is the greedy Goans who are selling agricultural land

and pulling down ancestral homes, and that the local government has no vision.

What escapes her is that Goans are all too often subject to forces not within their

control. Goans are trapped in an economy that, rather than working on producing

more varied opportunities for the locals, has for decades now relied

exclusively on tapping the extractive industries of either tourism or mining,

or on overseas remittances. While the tourist economy has produced huge profits

for some, incomes have not risen to keep pace with the increased cost of

living. In such a context, there are two options that will assure people

without the material resources or skill sets to fuel social mobility of persons

who cannot achieve betterment in Goa. The first is the sale of land to persons

in search of the fabled Goan lifestyle. The second is migration in search of

gainful and respectable employment. The irony is that the critique of the Portuguese

presence in Goa was that they failed to develop a viable economy, which

required people to migrate to earn a living that would assure them and their

families of a higher standard of living. Indeed, for the vast majority of the

population life under Portuguese rule was experienced more as life under

landlord rule. And this Goan lifestyle was no idyll. It was only through

migration that they could economically emancipate themselves. It was only with

the economic liberation possible through migration that Goa, now a place to

return for the summers, was constructed as an idyll. As it turns out, the

transition to Indian rule has not changed much, as many Goans are still forced to migrate.

Yet it is not economics alone that

Goans are trapped by but, the political system itself. There is a clear

understanding among the many groups in the territory that this system is not

delivering good governance and that there is a need for dramatic change. In

their imitation of Britain, British Indians adopted the

unsophisticated first-past-the-post system of determining political

representatives. As Dr. Ambedkar pointed out, the ills of the system are such

that it

does not allow for marginalized groups to find a voice in the legislature. Even

though there are moves to shift to a system of proportional representation, it

seems unlikely that there will be a change anytime soon. Thus, Goans are chained

to a political structure that they had no say in determining, and that clearly

does not work for their territory, given that it reproduces persons who

represent majoritarian politics. One wonders whether Goan politics may not have

been dramatically different if the people of the territory were allowed to

innovate with a proportional representation system followed in Portugal.

But Kapoor’s text is not merely

illustrative of the problem that Goans have with the Indian elites. Rather, it exposes

the colonial relationship of these elites with marginalized Indian populations.

The trouble with the Indian elites is that they do not see themselves as a part

of the political processes of the subcontinent, believing themselves too good

for the rest of the citizens of India. Indeed, this is part of their adoption

of the colonial gaze. These elites see the residents of the rest of the

continent as a strange race that requires firm governance. The review

of Kapoor’s book by Prashansa Taneja makes this quite obvious when she

reports, “more often than not, she gives into the temptation to exoticise

Delhi, and India, for the reader. Many Indian women cover their heads on a

daily basis, but when Idha [the character in Kapoor’s book] does so at a Sufi

shrine, she feels she becomes ‘Persian, dark-eyed, pious and transformed’.” One

could argue that she succumbs to the use of clichés precisely because like

other members of her class, Kapoor looks at the people in the city of Delhi,

through a gaze adopted from the Raj.

Goa and Goans are locked in an

unequal and unfair colonial relationship with India. Until and unless this

inequality and injustice are resolved, and the relationship is made more equal

– indeed, until the colonial equation at the heart of the imperial Indian

project is resolved – Goa and Goans may be doomed to destruction. Kapoor’s text

is offensive precisely because she is blind to these facts, and while also

being blind to her own privilege is completely oblivious to the extent to which

her article is a gripe about the loss of her own privileges. Kapoor’s problem

seems to lie in the fact that with other Indians, and not just other elites but

all sorts, coming to play with her toy, the party has been ruined. While Kapoor

may be able to trip off to some other island paradise and live the life of the

wandering elite, where, pray, will the Goans go?

(A version of this post was first published in Raiot webzine on 17 Oct 2016)

_slider_main.jpg?1386696718)