| |

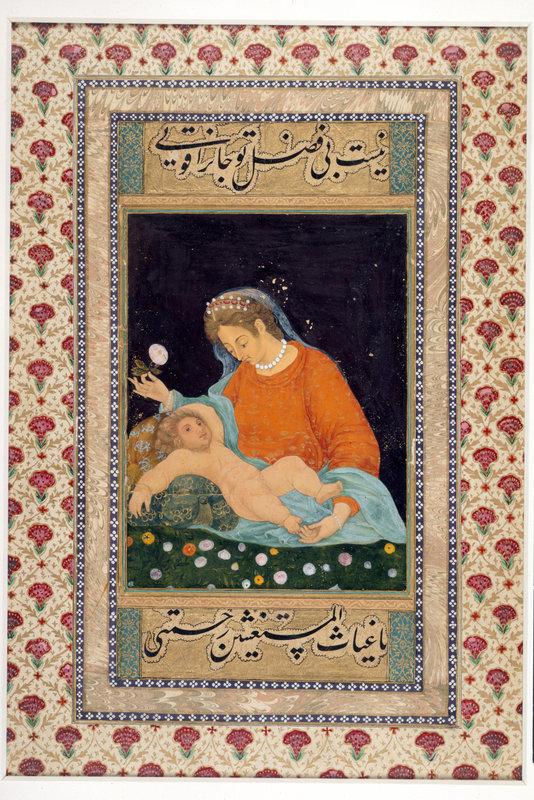

| Original illustration by Angela Ferrao |

For the moment

then, the crisis seemed to have receded. Nevertheless, the episode refreshed my

memory over two earlier episodes involving holidays. One is an event that lies

within the public domain, the other a personal memory that I would like to

share and reflect on.

The first episode

dates back a number of years, when the government of the then Chief Minister of

Goa, Manohar Parrikar, contemplated withdrawing the public holidays on the Good

Friday and the feast of St. Francis Xavier. As can be expected, there was a hue

and cry then too, until this controversial move was undone, with Parrikar later suggesting that the move had been an error.

The first episode

dates back a number of years, when the government of the then Chief Minister of

Goa, Manohar Parrikar, contemplated withdrawing the public holidays on the Good

Friday and the feast of St. Francis Xavier. As can be expected, there was a hue

and cry then too, until this controversial move was undone, with Parrikar later suggesting that the move had been an error.

The second

episode dates from the time when I was working with an NGO in Hyderabad. I

realised with some shock that this corporate-funded entity had not declared Eid

(I forget which of the two Eids it was) a holiday. On the contrary, it was

marked as an optional holiday. If one chose, for religious reasons, one could

take the day off, but the rest of the office would continue working. I also

recall being told that one could take the day off, but I would be merely eating

into my own stock of optional holidays. I recollect sensing the suggestion of

the threat that I would be compromising my days of Christian celebration were I

to take the day off to commemorate the feast.

I was quite

upset by this scenario. I had recently returned from Patna where I had a number

of Muslim friends and had been sucked into a series of Eids, weddings, and

other celebrations. Even though I was bereft of this network in Hyderabad, I could

not contemplate an Eid that was to be spent working, instead of feasting with

friends. It hurt, but rather than create trouble and stand up for a principle I

was not yet sure of, I went to work that Eid day, mournfully walking past

masses of men praying at the mosques along the route I took to work.

I was quite

upset by this scenario. I had recently returned from Patna where I had a number

of Muslim friends and had been sucked into a series of Eids, weddings, and

other celebrations. Even though I was bereft of this network in Hyderabad, I could

not contemplate an Eid that was to be spent working, instead of feasting with

friends. It hurt, but rather than create trouble and stand up for a principle I

was not yet sure of, I went to work that Eid day, mournfully walking past

masses of men praying at the mosques along the route I took to work.  These memories

were swirling around my head these past couple of days I realised that the

issue of cancelling holidays, or restricting these holidays is much more

important than showing disrespect or disregard for religious minorities. On the

contrary, such governmental actions ensure that religious boundaries are

hardened and religions are formed into water tight compartments. The learning

from Hyderabad was just that, you can choose to be a Catholic and take your

holiday, or you can choose to show solidarity with Muslims. We are not

preventing you from celebrating Eid, but you need to make a choice. Similarly,

had the feast of St. Francis Xavier continued to have lost its holiday, a great

number of Catholics would have still taken the day off to visit Old Goa and

venerate the relics of the saint. This option would perhaps not have been so

definite for those Goans who are not practicing Catholics but still venerate

St. Francis Xavier. It is possible that they would have continued with their

daily routines. Similarly had the holiday on Good Friday been cancelled it

would not only have complicated the possibility of having clear roads for the

public processions that mark Good Friday, it would also have complicated the

participation of non-Catholics, who light up the streets, and offer incense to

perfume the funeral path of Christ.

These memories

were swirling around my head these past couple of days I realised that the

issue of cancelling holidays, or restricting these holidays is much more

important than showing disrespect or disregard for religious minorities. On the

contrary, such governmental actions ensure that religious boundaries are

hardened and religions are formed into water tight compartments. The learning

from Hyderabad was just that, you can choose to be a Catholic and take your

holiday, or you can choose to show solidarity with Muslims. We are not

preventing you from celebrating Eid, but you need to make a choice. Similarly,

had the feast of St. Francis Xavier continued to have lost its holiday, a great

number of Catholics would have still taken the day off to visit Old Goa and

venerate the relics of the saint. This option would perhaps not have been so

definite for those Goans who are not practicing Catholics but still venerate

St. Francis Xavier. It is possible that they would have continued with their

daily routines. Similarly had the holiday on Good Friday been cancelled it

would not only have complicated the possibility of having clear roads for the

public processions that mark Good Friday, it would also have complicated the

participation of non-Catholics, who light up the streets, and offer incense to

perfume the funeral path of Christ.

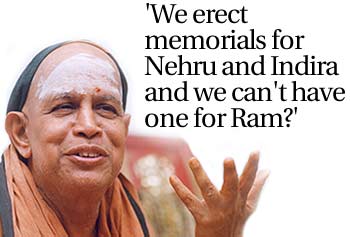

We must remember that we live in an environment where thanks to the threat of an aggressive Hindu nationalism, all religious groups have been hardening their identities and castigating what are called syncretic practices. When a government restricts a holiday, therefore, or fails to provide one, it is lending its own strength against these already existent social pressures. The issue of cancelling holidays therefore does not merely impact on the group for whom it is most significant. It impacts all, preventing communal celebrations, visits, exchange of sweets. It goes towards creating a fractured society.

It is in this

context that we should evaluate the clarifications of Smriti Irani, Minister

for Human Resources Development, on the issue of celebration of ‘Good

Governance’ day, as well as the subsequent note from the Prime Minister’s

Office that mandated various officers to mark ‘Good Governance’ day. What is clear is that rather than let Christmas

day be, the Central Government has identified the twenty-fifth of December as

the day to commemorate ‘Good Governance’ day. The essay competition will

continue apace even though the event will be restricted to submissions over the

internet. Further, various officers of the Government were expected to attend

and conduct commemorations linked to the theme of good governance.

It is in this

context that we should evaluate the clarifications of Smriti Irani, Minister

for Human Resources Development, on the issue of celebration of ‘Good

Governance’ day, as well as the subsequent note from the Prime Minister’s

Office that mandated various officers to mark ‘Good Governance’ day. What is clear is that rather than let Christmas

day be, the Central Government has identified the twenty-fifth of December as

the day to commemorate ‘Good Governance’ day. The essay competition will

continue apace even though the event will be restricted to submissions over the

internet. Further, various officers of the Government were expected to attend

and conduct commemorations linked to the theme of good governance. What this

effectively amounts to is providing an alternative to the celebrations of

Christmas that have become a major feature across India. One does not need to

be Christian, nor indeed have Christian friends to celebrate the day. Regardless of their religious persuasion, people engage in secular celebrations of this feast by organising Christmas

parties, arranging visits from Santa Claus and the like. The fact is that thanks

to a variety of factors, a number of Indians, and especially urban and upwardly

mobile Indians are ‘culturally Christian’. They have imbibed many Christian

and/or western cultural traditions and celebrate them as if these traditions

are their own. That these aspects are not strictly religious is not important,

it is in fact exactly the point, that the festival has ceased to be religious

alone, but is a cross-communal secular festival. Indeed, if one is to take the

historical novel, The Mirror of Beauty

seriously, Christmas, or Bada Din was a significant festival in Delhi by the time of the last Mughal emperor, and

avidly celebrated by the Mughal elites.

What this

effectively amounts to is providing an alternative to the celebrations of

Christmas that have become a major feature across India. One does not need to

be Christian, nor indeed have Christian friends to celebrate the day. Regardless of their religious persuasion, people engage in secular celebrations of this feast by organising Christmas

parties, arranging visits from Santa Claus and the like. The fact is that thanks

to a variety of factors, a number of Indians, and especially urban and upwardly

mobile Indians are ‘culturally Christian’. They have imbibed many Christian

and/or western cultural traditions and celebrate them as if these traditions

are their own. That these aspects are not strictly religious is not important,

it is in fact exactly the point, that the festival has ceased to be religious

alone, but is a cross-communal secular festival. Indeed, if one is to take the

historical novel, The Mirror of Beauty

seriously, Christmas, or Bada Din was a significant festival in Delhi by the time of the last Mughal emperor, and

avidly celebrated by the Mughal elites.

Given the kind

of pressure that Indian society places on students to excel and gain laurels,

one can imagine that children would be encouraged, if not pressured, to take

part in a national competition that could get them national recognition.

Remember we live in a country where even a certificate of participation is

regarded as useful. As such, having a competition at the time of the Christmas

holidays, with a submission on Christmas day, no matter that the submission can

be made virtually, ensures that one has created a substantial diversion from

the pleasures, and significance, of Christmas. In addition to these competitions,

the low-key government commemorations of good governance that continued even while the holiday was still officially on clearly indicate that

the conspiracy to steal Christmas is, therefore, still on.

It should be

noted, however, that it is not only the BJP government that is engaged in a

project that dismisses Christmas. A variety of organisations in India,

including academic and non-governmental, as well as those patronised by the

nominally secular-liberals think nothing of hosting significant retreats

immediately prior to, or soon after Christmas day. This scheduling ensures that

very often Christians have to either opt out of Christmas, or the event, or

spend a good part of Christmas day in travel. And, as I pointed out earlier,

this callous scheduling does not impact Christians alone, but fractures the

possibility of non-Christians in participating in what is a wonderful feast of

familial gathering. The loss is communal.

We live in a

country where the plethora of holidays we enjoy is often castigated. Over the

year these holidays have been vilified merely as days free from work. What this

vilification does not recognise is that holidays are a way for us to indicate

that an event is important enough for us to take time off work and engage with

each other. Even if we choose to not engage with other communities, the holiday

continues to be a mark that this other community is important. It is this

tradition of honouring those who are unlike us that is at stake when holidays

are so callously countermanded.

Feliz Natal! Have a blessed and joyous

Christmas season!

(A version of this text was first published in the O Heraldo dated 26 Dec 2014)