Some days ago I found myself

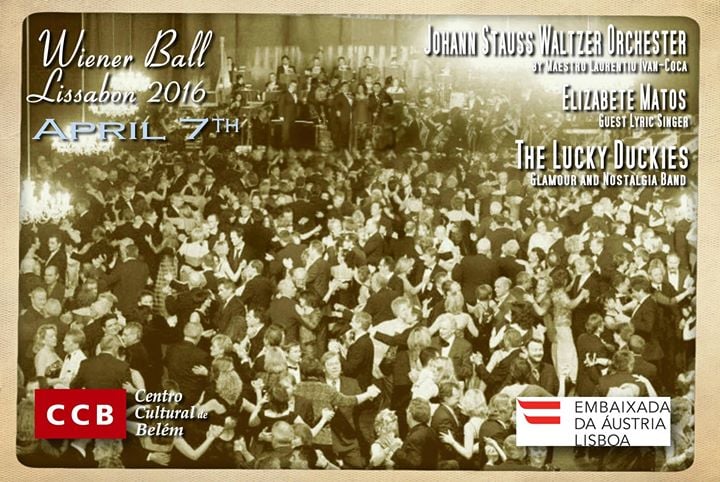

invited to a ball in Lisbon hosted by the Austrian embassy in Portugal. Revived

after more than a decade, the current initiative was conceived of a way to generate

funds for deserving causes. In this inaugural year, funds were raised in

support of A Orquestra Geração,

which is the Portuguese application of the El Sistema method

created in Venezuela. Another objective was to introduce Portuguese

society to aspects of Austrian, and in particular Viennese, culture.

Some days ago I found myself

invited to a ball in Lisbon hosted by the Austrian embassy in Portugal. Revived

after more than a decade, the current initiative was conceived of a way to generate

funds for deserving causes. In this inaugural year, funds were raised in

support of A Orquestra Geração,

which is the Portuguese application of the El Sistema method

created in Venezuela. Another objective was to introduce Portuguese

society to aspects of Austrian, and in particular Viennese, culture. It was because the event was

billed as a Viennese ball that I have to confess being somewhat concerned about

the protocol at the event. For example, would there be dance cards? It was when

I actually got immersed into the ball, however, that I realized that I was not

in foreign territory at all. The ball followed a pattern not merely of

contemporary wedding receptions and dances in Goa, but also approximated quite

well the manners that had been drilled into me as a young boy, when first

introduced by my parents to ballroom dancing. One requested a lady – any lady –

to dance, accompanied her on to the floor, and at the end of the dance, one

thanked her, applauded the orchestra or band, and returned one’s companion to

her seat. In other words, there was, structurally, not much at this ball that I,

as a Goan male, had not already been exposed to.

It was because the event was

billed as a Viennese ball that I have to confess being somewhat concerned about

the protocol at the event. For example, would there be dance cards? It was when

I actually got immersed into the ball, however, that I realized that I was not

in foreign territory at all. The ball followed a pattern not merely of

contemporary wedding receptions and dances in Goa, but also approximated quite

well the manners that had been drilled into me as a young boy, when first

introduced by my parents to ballroom dancing. One requested a lady – any lady –

to dance, accompanied her on to the floor, and at the end of the dance, one

thanked her, applauded the orchestra or band, and returned one’s companion to

her seat. In other words, there was, structurally, not much at this ball that I,

as a Goan male, had not already been exposed to. This encounter made me realize

once again, the validity of the argument that my colleagues at the Al-Zulaij Collective and

I have been making for a while now; that Goans,

or at least those familiar with the Goan Catholic milieu, are in fact also

European. Given the fact that Goans participate in European culture, and have

been doing so for some centuries now, denying this European-ness would imply falling

prey to racialised thinking that assumes that only white persons born in the continent of Europe, are European.

This encounter made me realize

once again, the validity of the argument that my colleagues at the Al-Zulaij Collective and

I have been making for a while now; that Goans,

or at least those familiar with the Goan Catholic milieu, are in fact also

European. Given the fact that Goans participate in European culture, and have

been doing so for some centuries now, denying this European-ness would imply falling

prey to racialised thinking that assumes that only white persons born in the continent of Europe, are European. To make this argument is not the

result of a desperate desire to be seen as European, but to assert a fact. One

also needs to make this assertion if one is to move out of the racialised

imaginations that we have inherited since at least the eighteenth century. It

is necessary to indicate that European-ness is not a culture limited to a

definite group, but like other cultures, is a model of behavior, in which one

can choose to participate in. And one chooses to participate in this

cultural model because the fact is that, whether we like it or not, this is the

dominant cultural model in the world. The choice then is not determined by a

belief in the model’s inherent superiority, it is simply a matter of pragmatic

politics.

To make this argument is not the

result of a desperate desire to be seen as European, but to assert a fact. One

also needs to make this assertion if one is to move out of the racialised

imaginations that we have inherited since at least the eighteenth century. It

is necessary to indicate that European-ness is not a culture limited to a

definite group, but like other cultures, is a model of behavior, in which one

can choose to participate in. And one chooses to participate in this

cultural model because the fact is that, whether we like it or not, this is the

dominant cultural model in the world. The choice then is not determined by a

belief in the model’s inherent superiority, it is simply a matter of pragmatic

politics.

Some days before the ball, I intimated

a continental Portuguese friend about this upcoming event, and the fact that I

was on the lookout for a place I could rent a tailcoat from. She sneered. The

suggestion in the sneer was, why do you have to become someone you are not. One

should remain true to one’s culture, and not try to engage in the culture of

others, or in other words, not engage in social climbing. The response was

upsetting, but not particularly out of the ordinary. This is, in fact, a standard

response, one that derives directly from our racialised imaginations. There is

this misplaced idea that when we participate in one cultural model, say the

European, one is abandoning other cultural models, and, more importantly, that non-whites

would always be on the back foot when faced with European culture. A look at

the cultural practices of Goan Catholics, however, will demonstrate the

ridiculousness of the proposition.

Goan Catholics have not only

taken up Western European cultural forms, but in fact excelled at them. In

doing so, they have not abandoned other cultural models, particularly the

local, but in fact rearticulated both these models at the same time. One has to

merely listen to the older Cantaram (Concani language music) regularly played

by the All India Radio station in Goa, to realize the truth of this assertion.

Take the delightful song “Piti Piti Mog”,

crafted by the genius Chris Perry and Ophelia, for example. Set to a waltz, the

song talks of the desires and sexuality of a Goan woman. The emotions are

honest to her social location. There is no betrayal of the local here, even as

Perry articulates it within an international idiom. Indeed, one wonders if

there is much of a difference between this song, and the soprano aria “Meine Lippen, sie küssen so heiß”.

From the opera Giuditta, and featured at the Viennese Ball, this aria also

sings of the sexuality of a young woman in her prime.

There are some who would argue

that what has been described above is not participation in a cultural model,

but in fact mere mimicry, or at best syncretism or hybridity. To put it

bluntly, Goans are mere copycats, there is nothing

original in what they do. Indeed, a good portion of the post-colonial academy

would describe the examples I proffer as syncretism or mimicry. To such critics

my question is this, were the young Portuguese women and men, making their

social debut in the ball, not also participating in an etiquette that is not

quite Portuguese? The waltz itself, that great institution of the Viennese

balls, originated in Central Europe. Does their participation pertain to the

category of mimicry, and syncretism, or is it somehow an authentic performance?

To suggest that it is, would be to fall right into the racist paradigm where

things European appropriately belong to whites, and the rest are merely engaging

in impotent mimicry. The anti-racialist argument would recognize that all of

these groups, whether continental Portuguese, or Goans (indeed also Portuguese

by right), are participating equally in a common cultural model, each of them

giving a peculiar twist to the model in their performance, all of them

authentic.

Another challenge to my argument

would perhaps emerge from Indian nationalists. If no one culture is authentic,

and one merely choses to participate in random cultural models, why privilege

the European? Why not join in the Indian

cultural model? In the words of a passionate young man from the Goan village of

Cuncolim I once interacted with, why not prefer your own people over foreigners? At that interaction I pointed out that crafting

the choice in terms of Us Indians,

versus Them Europeans, and stressing

a biological or genetic proximity was falling back into the very racist

equation we should be trying to be exit.

To begin with, this construction

of the Indians, versus Portuguese works only because like most Indian

nationalists he privileges the terrestrial contiguity of Goa to the

subcontinent. The art critic Ranjit Hoskote phrased a succinct response to this

claim in the curatorial

essay for the exhibition Aparanta

(2007) when he argued “Geographical contiguity does not mean that Goa and

mainland India share the same universe of meaning”. In highlighting Goa’s

Lusitanian links, Hoskote rightly pointed out that the seas were not a barrier

to conversation but a link, and maritime connections are no less powerful than

the terrestrial. Indeed, while connected to Europe, Goa has been an equal part

of the Indian Ocean world, often sharing as much, if not more, with the East

coast of Africa than with the Gangetic plains; that privileged location of

Indian-ness. Terrestrial contiguity apart, this nationalist argument also

succeeds because it willfully ignores a legal history, of Goans

being Portuguese citizens, and hence European, in favour of a biased

construction of cultural history.

To begin with, this construction

of the Indians, versus Portuguese works only because like most Indian

nationalists he privileges the terrestrial contiguity of Goa to the

subcontinent. The art critic Ranjit Hoskote phrased a succinct response to this

claim in the curatorial

essay for the exhibition Aparanta

(2007) when he argued “Geographical contiguity does not mean that Goa and

mainland India share the same universe of meaning”. In highlighting Goa’s

Lusitanian links, Hoskote rightly pointed out that the seas were not a barrier

to conversation but a link, and maritime connections are no less powerful than

the terrestrial. Indeed, while connected to Europe, Goa has been an equal part

of the Indian Ocean world, often sharing as much, if not more, with the East

coast of Africa than with the Gangetic plains; that privileged location of

Indian-ness. Terrestrial contiguity apart, this nationalist argument also

succeeds because it willfully ignores a legal history, of Goans

being Portuguese citizens, and hence European, in favour of a biased

construction of cultural history.

The most important support to nationalism, of

course, comes from the racism inherent in the post-colonial order which is

built on recognizing cultural difference managed by nationalist elites rather

than stressing continuing connections. Indeed, as I go on to elaborate below,

to some extent everybody participates in the European model in today’s world –

in clothes and speech and education and science, and so forth. But the control

of nationalist elites over the national space, and the international

post-colonial order itself, would be threatened by such recognition. It is

therefore necessary that while quotidian affairs run along European lines, the

extraordinary is sanctified by the irruption of the national. Thus, while

Indians wear pants and shirts every day, they believe that special days call

for traditional garb, like kurtas.

The Goan bucks this trend by privileging special moments with a lounge suit. In

other words, Goan culture celebrates what is overtly European, which is what

the Indians don’t like as its wrecks the nationalist posturing of not

participating in European culture.

To those who would simply ask,

why not exert a choice in favour of the Indian, the answer is two-fold. The

first, is that there are many Goans, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, who are

in fact choosing the Indian model. They do so because they see that this is

where local power lies. Behaving like Indians, they believe that they can make

their way better in the Indian world. Others, however, recognize the

limitations of the Indian model. It can take you only so far. Upwardly mobile

Indians themselves recognize that they have to perform by different rules when

they emigrate. Worse, the captains of industry will tell you that they have to

perform by European rules whenever they meet with their compatriots from other

parts of the world. As indicated before, where the European cultural model

dominates the world, it is merely pragmatic politics to follow that model.

Finally, it is precisely the lack of social mobility that makes many wisely

avoid the Indian cultural model. The very attraction of the European model is

that practically any person can learn to perform in it and be accepted as

authentic. Indian models are so limited to Hinduism

and caste that one cannot hope to make this parochial model work as a tool

of social mobility. Indeed, one could ask whether there in an Indian cultural model at all, and if it

is not just a savarna/brahmanical model?

To those who would simply ask,

why not exert a choice in favour of the Indian, the answer is two-fold. The

first, is that there are many Goans, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, who are

in fact choosing the Indian model. They do so because they see that this is

where local power lies. Behaving like Indians, they believe that they can make

their way better in the Indian world. Others, however, recognize the

limitations of the Indian model. It can take you only so far. Upwardly mobile

Indians themselves recognize that they have to perform by different rules when

they emigrate. Worse, the captains of industry will tell you that they have to

perform by European rules whenever they meet with their compatriots from other

parts of the world. As indicated before, where the European cultural model

dominates the world, it is merely pragmatic politics to follow that model.

Finally, it is precisely the lack of social mobility that makes many wisely

avoid the Indian cultural model. The very attraction of the European model is

that practically any person can learn to perform in it and be accepted as

authentic. Indian models are so limited to Hinduism

and caste that one cannot hope to make this parochial model work as a tool

of social mobility. Indeed, one could ask whether there in an Indian cultural model at all, and if it

is not just a savarna/brahmanical model? This lack of social mobility is

best illustrated by an example from Goa, where the Saraswats are a dominant

caste. Speaking with a Saraswat gentleman at a Nagari Konkani event, he

indicated to me how pleased he was with the response to the elocution

competitions organized by the Nagari Konkani groups. Many a times the winners

were Catholic girls. “But their accent is so good”, he shared with me, “one

cannot even tell that they are Catholics!” Where Nagari Konkani is largely

based on the speech of the Saraswat caste, one is forever trapped into behaving

like a Saraswat, and distancing

oneself from one’s natal behaviours. One can never be Saraswat unless one is born into the caste. A good part of the

Indian model is similarly pegged according to the behavior of the dominant

castes of various regions. This model has been created not necessarily to

enable a democratic project, but to ensure their continued dominance within

post-colonial India. As such, they will

put a person in their place when a person from a non-dominant caste performs

effectively. The adoption of the European model, however, is not restricted to birth

precisely because it has been adopted so universally. The adoption and

occupation of this model by diverse groups has thus ensured that its very form now

allows for local variation. Indeed, it needs to be pointed out that the model

is very dynamic. Let us not forget that at one point of time one was expected to

speak Queen’s English on the BBC, but

the same platform, at least in its local transmission, has now made space for a

variety of accents.

This lack of social mobility is

best illustrated by an example from Goa, where the Saraswats are a dominant

caste. Speaking with a Saraswat gentleman at a Nagari Konkani event, he

indicated to me how pleased he was with the response to the elocution

competitions organized by the Nagari Konkani groups. Many a times the winners

were Catholic girls. “But their accent is so good”, he shared with me, “one

cannot even tell that they are Catholics!” Where Nagari Konkani is largely

based on the speech of the Saraswat caste, one is forever trapped into behaving

like a Saraswat, and distancing

oneself from one’s natal behaviours. One can never be Saraswat unless one is born into the caste. A good part of the

Indian model is similarly pegged according to the behavior of the dominant

castes of various regions. This model has been created not necessarily to

enable a democratic project, but to ensure their continued dominance within

post-colonial India. As such, they will

put a person in their place when a person from a non-dominant caste performs

effectively. The adoption of the European model, however, is not restricted to birth

precisely because it has been adopted so universally. The adoption and

occupation of this model by diverse groups has thus ensured that its very form now

allows for local variation. Indeed, it needs to be pointed out that the model

is very dynamic. Let us not forget that at one point of time one was expected to

speak Queen’s English on the BBC, but

the same platform, at least in its local transmission, has now made space for a

variety of accents.

The policing of cultural

boundaries is one of the silent ways through which racism continues to flourish.

It is in partly in the breaching of cultural boundaries that racism can be

broken. Further, it is in operating within the idiom of power, and then filling

the forms of power with differing contents, that negotiation with power

operates and one moves from the margins of power towards the centre. In this

project, Goans are past masters. Viva Goa!

(A version of this text was first published in Raiot on 26 April 2016)