There was a commotion in Cyberia a couple of weeks ago, around some of the observations made by Adv. Uday Bhembre in the course of an interview. The statement that caused so much of consternation was made in explanation of why Adv. Bhembre opposes grants-in-aid to schools that impart primary education in English. To give a sense of what irked the cyber-Goemcars, the statement by Adv. Bhembre is extracted in some length below.

There was a commotion in Cyberia a couple of weeks ago, around some of the observations made by Adv. Uday Bhembre in the course of an interview. The statement that caused so much of consternation was made in explanation of why Adv. Bhembre opposes grants-in-aid to schools that impart primary education in English. To give a sense of what irked the cyber-Goemcars, the statement by Adv. Bhembre is extracted in some length below.

“Let me narrate to you a glaring incident that happened in my life. When I was the Independent MLA of Margao in 1985-89, I was invited by the Grace Church Parish to speak to the youth on Culture. The audience comprised of young boys between 20 to 25 years of age, to my surprise there were no girls. I don't know. The three preceding speakers spoke in English and I spoke in Konkani. During the question and answer session the Priest requested them to ask questions, I too requested them. But they did not respond, later the priest told me that if I had spoken in English perhaps they would have understood. Then I asked him (priest) why they did not understand. “They did not understand because you spoke in Konkani and not English”, the priest replied. It was all the more astonishing that all of these youth were Goans and did not understand or might not want to speak in Konkani. And if that was situation in 1988 what would it be now? So that kind of a situation is bound to develop according to me if English is encouraged at primary level itself in Goa."

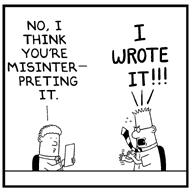

Adv. Bhembre is perhaps not the first person to face this strange situation, given the two other similar situations this column will narrate, but perhaps he (and the friendly parish priest) may have misinterpreted the situation they faced.

Adv. Bhembre is perhaps not the first person to face this strange situation, given the two other similar situations this column will narrate, but perhaps he (and the friendly parish priest) may have misinterpreted the situation they faced.

The first of the situations took place in a training session for rookie ‘announcers’ for the AIR. The crowd was largely English speaking and faced with a Konkani speaking staff member of the radio station. The session was a nightmare though, for not a single question presented by the trainer drew a response from the audience. It seemed as if the explanation articulated by Adv. Bhembre, would have held good here as well, a crowd of young Goans, brought up to be English speaking, and yet unable to speak in Konkani.

Subsequent to the training session, asking one of the members of the audience if it was the case that she did not speak or understand Konkani, drew a fierce response. ‘Ofcourse not!’ she responded, opening her eyes wide. ‘I sing in Konkani, I do the readings in Church, I can manage quite well in Konkani. But his (referring to the trainer) Konkani is different no?’

Subsequent to the training session, asking one of the members of the audience if it was the case that she did not speak or understand Konkani, drew a fierce response. ‘Ofcourse not!’ she responded, opening her eyes wide. ‘I sing in Konkani, I do the readings in Church, I can manage quite well in Konkani. But his (referring to the trainer) Konkani is different no?’

This response affirmed the capacity of the silent audience to speak and understand Konkani, but it provided no reason as to why, because there were two different Konkanis in operation, the response of one of the Konkani speakers should be silence. This reason was provided in another conversation, this time round with a Catholic priest. In the course of our conversations around Konknai, this priest indicated a strong friendship he enjoyed with a Hindu gentleman. At one point however, the priest recounted that he was reproached by his friend; ‘Why is it that you never speak to me in Konkani’ the friend asked. To this question the priest responded that he felt ashamed, since his friend’s Konkani was so perfect, so pure, whereas his own was the ‘impure’ version that the Catholics speak.

This response affirmed the capacity of the silent audience to speak and understand Konkani, but it provided no reason as to why, because there were two different Konkanis in operation, the response of one of the Konkani speakers should be silence. This reason was provided in another conversation, this time round with a Catholic priest. In the course of our conversations around Konknai, this priest indicated a strong friendship he enjoyed with a Hindu gentleman. At one point however, the priest recounted that he was reproached by his friend; ‘Why is it that you never speak to me in Konkani’ the friend asked. To this question the priest responded that he felt ashamed, since his friend’s Konkani was so perfect, so pure, whereas his own was the ‘impure’ version that the Catholics speak.

This deep-rooted sense of inferiority of their version of Konkani is the reason for this silence among vast sections of the Konkani-speaking Catholic population in Goa. This sense of inferiority is not the result only of the dominance of the Antruzi variant since the legislation of the Official Language Act in 1987. The hierarchy that privileges Antruzi is the result of larger theoretical understandings that have been deeply grounding in society, since they came into operation since the nineteenth century, though to be sure these understandings have been underlined by teachings in school since 1987.

This deep-rooted sense of inferiority of their version of Konkani is the reason for this silence among vast sections of the Konkani-speaking Catholic population in Goa. This sense of inferiority is not the result only of the dominance of the Antruzi variant since the legislation of the Official Language Act in 1987. The hierarchy that privileges Antruzi is the result of larger theoretical understandings that have been deeply grounding in society, since they came into operation since the nineteenth century, though to be sure these understandings have been underlined by teachings in school since 1987.

This silence is not a uniquely Goan phenomenon however. This response in silence has famously been highlighted by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in his exploration of the power dynamics among dialects within France and their relationship with ‘official French’. Bourdieu points out that as a result of the active diminishing of the legitimacy of other variants of the language, and the stress of auto-correction that persons who do not naturally possess a facility with the official variant encounter, there is a tendency of working-class children to eliminate themselves from the educational system, or to resign themselves to vocational courses and training. He also pointed out to the unease and ‘the hesitation leading to silence’, which may overcome individuals from lower-class backgrounds on occasions defined as official.

The silence among Adv. Bhembre’s audience is not therefore the result of not knowing Konkani, but of the shame that has been drilled into Catholic society (not least by their own intellectuals from the nineteenth century on) that the Konkani that they speak is not proper Konkani. This logic is not limited only to those sections of the pro-Konkani world that favour Antruzi as the finest form of spoken Konkani. Take for example the spelling of the Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr, which seems to replicate the Sanskritized sounds of Antruzi, rather than the broader sounds typical to the Concanim spoken among Catholics in Goa. From Bourdieu’s work it would appear that introduction of the ‘official variant’ into schooling compound the problem, since it provides a systemic production of this shame. From this logic, it would appear therefore that rather than addressing the problem Adv. Bhembre mistakenly perceived; schooling in Konkani is one of the systemic forms of perpetrating the shame and driving more and more young people away from Konkani. The solution that Adv. Bhembre seeks therefore, may come from routes other than the compulsory education in a language form that many students do not in fact identify with.

The silence among Adv. Bhembre’s audience is not therefore the result of not knowing Konkani, but of the shame that has been drilled into Catholic society (not least by their own intellectuals from the nineteenth century on) that the Konkani that they speak is not proper Konkani. This logic is not limited only to those sections of the pro-Konkani world that favour Antruzi as the finest form of spoken Konkani. Take for example the spelling of the Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr, which seems to replicate the Sanskritized sounds of Antruzi, rather than the broader sounds typical to the Concanim spoken among Catholics in Goa. From Bourdieu’s work it would appear that introduction of the ‘official variant’ into schooling compound the problem, since it provides a systemic production of this shame. From this logic, it would appear therefore that rather than addressing the problem Adv. Bhembre mistakenly perceived; schooling in Konkani is one of the systemic forms of perpetrating the shame and driving more and more young people away from Konkani. The solution that Adv. Bhembre seeks therefore, may come from routes other than the compulsory education in a language form that many students do not in fact identify with.

The provision of solutions to Adv. Bhembre’s pickle is not the purpose of this column. The purpose of this column was to stress that there are multiple ways in which silence can be read. Silence is not always a sign of stupidity or a lack of knowledge. Silence can be the mark of shame, or unease, or equally of disobedience. The silence in response to Konkani speakers among Concanim speaking audiences could very well be one among these many reasons. Indeed, we can safely say that it is not one of either stupidity or lack of knowledge.

The provision of solutions to Adv. Bhembre’s pickle is not the purpose of this column. The purpose of this column was to stress that there are multiple ways in which silence can be read. Silence is not always a sign of stupidity or a lack of knowledge. Silence can be the mark of shame, or unease, or equally of disobedience. The silence in response to Konkani speakers among Concanim speaking audiences could very well be one among these many reasons. Indeed, we can safely say that it is not one of either stupidity or lack of knowledge.

(A version of the post was first published in the Gomantak Times 31 Aug 2011)

The People’s Linguistic Survey of India has recently found that India lost 200

languages in the last 50 years.

The most comprehensive survey to have been conducted in the last 80 years, it

suggests that there is a need to “[maintain] organic links between scholarship

and the social context.” The current modus, especially with regard to the

Konkani language, which imposes an alien dialect of the dominant castes on

initial learners, is bound to contribute to the alarming trend of diminishing

language diversity as cited by this survey. As pointed out earlier, this

complicates the voluntary adoption of Konkani. Indeed, a class and caste

sensitive reading of the controversy that is briefly discussed below reveals

that it is precisely the imposition of an alien form of Konkani on the

population (a population that would have normally opted for education in

Konkani) that is partly responsible for the demand for English as a state-supported

MoI.

The People’s Linguistic Survey of India has recently found that India lost 200

languages in the last 50 years.

The most comprehensive survey to have been conducted in the last 80 years, it

suggests that there is a need to “[maintain] organic links between scholarship

and the social context.” The current modus, especially with regard to the

Konkani language, which imposes an alien dialect of the dominant castes on

initial learners, is bound to contribute to the alarming trend of diminishing

language diversity as cited by this survey. As pointed out earlier, this

complicates the voluntary adoption of Konkani. Indeed, a class and caste

sensitive reading of the controversy that is briefly discussed below reveals

that it is precisely the imposition of an alien form of Konkani on the

population (a population that would have normally opted for education in

Konkani) that is partly responsible for the demand for English as a state-supported

MoI. Many

people in Goa choose to be educated in English for practical purposes. It

allows them to avail of higher chances for employment, not merely in Goa, but

across the world. A good portion of the Goan population gains employment

through migration. Given that Goa benefits from the foreign exchange remitted

by those that work beyond India’s borders, and also that it is the

Constitutional obligation of the State to support citizens in their endeavours,

the government must support these attempts at ensuring future employability.

Many

people in Goa choose to be educated in English for practical purposes. It

allows them to avail of higher chances for employment, not merely in Goa, but

across the world. A good portion of the Goan population gains employment

through migration. Given that Goa benefits from the foreign exchange remitted

by those that work beyond India’s borders, and also that it is the

Constitutional obligation of the State to support citizens in their endeavours,

the government must support these attempts at ensuring future employability.