Despite all the good that they

bring, in terms of revelations of the dirty underbelly of our society,

governmental operation or otherwise, there is always this nagging feeling that

all is not quite right with the route of the ‘sting operation’. Our legal

system, like most today, is based on the centrality of the conscious subject.

Thus for example, one cannot compel an individual to give evidence against oneself.

Despite the unpopularity of this idea among various segments of people, to do

otherwise would result in fairly authoritarian systems, which would absolutely

undermine the freedom and dignity of the individual.

Faithful readers of the Gomantak

Times will realize that reference is being made here to the

sting operation conducted by the journalist Mayabhushan Nagvekar against the ‘paid news’

services that the

O Heraldo seems to offer. The point of this column is not to

condemn Nagvekar for his operation, nor to hastily condemn the O Heraldo before

the whole episode has been investigated and run its course. The aim of this

column is to explore the suggestions made by the editor of the O Heraldo in his

response, to Nagvekar’s charge.

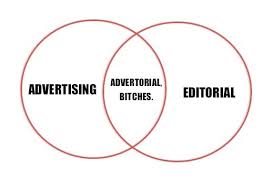

The editor's statement to the allegations by Nagvekar, published on the website of

MXMIndia, suggested that ‘Herald is the only newspaper which used the

tag “advertorial” on top of their news pages so that the difference between

editorial and advertorial is clearly established.’ This suggestion seeks to

draw a line between the practices effected by O Heraldo and other newspapers.

The editor is suggesting here, that in doing so, O Heraldo, is in fact the more

ethical of the pack. If this is true, this is a fair statement to make.

However, the question we should be asking is whether it is ethical in the first

place to allow “advertorials” in a newspaper, whether indicated as such, or

simply placed there for the unsuspecting to swallow, hook, line and sinker.

It appears that we are not

surprised today when a newspaper is seen as a commercial institution, geared toward

generating a profit for its owners. We must not forget however, that the

newspaper has come into this position of being able to generate profit

primarily because it served larger ends. This larger end was the creation of

the informed public sphere, or civil society, the basis of the modern bourgeois

democracy.

The very notion of the public

sphere is based on numerous ideas of honour.

The idea that ‘the public’ is of value, is educated, thus worthy of

honour demonstrated in the form of presenting one’s idea passionately, without

guile or artifice. This presentation of an opinion also relied on the idea of

the honour of the writer, the journalist, who staked his honour on this

guileless presentation. Finally, is the idea of civil society, where unlike in

the

ancien regime where decisions

were made without reference to the people, reached through private

arrangements, governance would be effected through the results of open

discussion.

The newspaper served thus as a

mouth-piece for ideological groups, each group proclaiming its position,

creating through this process of publication, and reading, and subsequent

response, the public sphere, a democratic space that could be relied on by the

Government to carry on its task of responsible and responsive governance.

Profit comes late into this equation, initially as a means to sustain an

initiative, and convert a good idea, into an institution. The newspaper sold

itself initially on the idea that what was being presented was an idea,

unburdened by guile, personal or corporate profit. Indeed, the respect, the

almost unparalleled access that the journalist receives is based on this

history, this expectation that the journalist is representing one’s honourable

opinion, one based on convictions, not on other extraneous circumstances.

One would be hard pressed to

suggest that the ‘advertorial’ matches up to this hallowed history. Under the

set of circumstances that create the advertorial, the journalist is not someone

who presents her impassioned opinion, or a balanced review of a position. On

the contrary, the journalist is now a hired hand. You pay money to the

journalist, and the journalist is commissioned like some portraiture artist to

paint a flattering likeness of the situation or person being presented to the reading

public.

There is another possibility

however that does not violate the political traditions of the newspaper as an

institution. This is when the advertorial is not crafted by a journalist who

works at the newspaper, but is merely a public relations agent. The job of this

agent is precisely to be this hired hand – though one hopes that such agents

also have ethical considerations that animate them. In such a case, the

advertorial is just another form of the kinds of advertisements that we

encounter on the birthday of a politician, of national events when we are

force-fed ‘news’ of the greatness of the politician whose anniversary is being

celebrated, or of the government in power. To be fair, this tradition, with the

dubious exception where the government places ads to lavish praise on the

electoral party in power, is a valid exercise of the public space created

through the newspaper. The purpose of the newspaper is to present a point of

view, and if the fan-base of a political leader seek to demonstrate why they

love him, this is a part of the newspaper’s political tradition. We need to remember however, that where the elected representative is treated as a king, relations between the representative and the electorate are not the ideal relationship one imagines where representative is responsible to the electorate, or to a wider public, but one between subject and King.

Where the advertorial steps

outside of the political tradition is when it takes up editorial space proper.

When money alone determines what becomes news and what not. In the cynical world

of late capitalism this position may not be shocking, but as idealist

democrats, we reserve our right to be shocked by this practice. We reserve this

right to be shocked because the point of a democracy is that whether rich or

poor, everyone has the equal right to speak and to be heard. In a democracy,

the poor especially have a right to have access to institutional frameworks

that will speak truth to power. When money begins to start determining what

makes it to the editorial page and what not, then democracy is in big, big

trouble. When money determines whether a citizen is able to prove her point, or

not, then democracy is in even deeper trouble.

Given the age of the O Heraldo, and the rich political history of

Goa that it represents, we owe to it the opportunity of believing it when its

Editor suggests that they were striving to be honest to the political

traditions of the newspaper when they indicate whether an item in the newspaper

is ‘advertorial’ or ‘editorial’. However, may we also suggest to the Herald,

that perhaps this distinction that they employ is riddled with problems, and it

behooves them to move beyond this practice that has so unfortunately taken root

in our democracy?

(A version of this post was first published in the Gomantak Times 2 Nov 2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment