Some weeks ago, the Universidade

Lusofona in Lisbon, under the aegis of the Association of Scientists of the

Lusophone space, organized a series of conferences around the theme ‘A

Construção da

Lusofonia na Era Pós-Colonial’ (The

construction of Lusofonia in the Post-colonial era).

One of the round-table discussions, to which I

was invited to speak, was on the theme of ‘Lusofonia in Goa: Today, and in the

future’.

At this roundtable I argued that Goa,

entirely for internal reasons of socio-political equity, ought to become a more

Lusophone (that is Portuguese speaking) space. However, prior to this, it was

important that we decenter metropolitan Portugal from this Lusophone project, or

else this project could turn out to have very serious neo-colonial

implications. The argument pointed out that we ought not to forget that

Lusofonia existed in the context of the prior establishment of both the

Commonwealth and Francophonie. Both of these two concepts and institutions

attempted to be post-colonial associations of a former empire, and yet both of

these projects contained a tendency to continue the hegemony of the

metropolitan center of these two empires. As long as we could decenter

metropolitan Portugal and not associate Portuguese exclusively with Portugal,

and create a forum for equal interaction among the pluri-statal members of this

linguistic group, Lusofonia was a great idea.

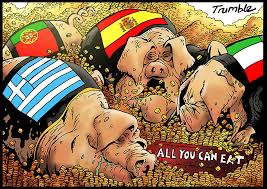

The shit hit the fan subsequent

to the presentation of this argument. One of the panelists abandoned his own

notes to passionately respond to my suggestions, arguing that Portugal did not

have the power, nor the will, to be a neo-colonial power. ‘Look at us now’ he

argued, pointing to the financial mess that the country was in. Another member

of the audience affirmed emphatically that in fact the neo-colonial

implications of Lusofonia simply did not exist, since the concept had been

actively discussed, and it was agreed that the language was not the marker of

imperial ambitions, but merely a symbol that seemed to connect the former

empire together.

The force of these arguments

should not have surprised, since there is a strong tendency among some metropolitan

Portuguese, even academics, to reject their complicity in anything colonial or

neo-colonial.

This affirmation is

possible since they make the simplistic assumption that their opposition to the

Estado Novo and its rhetoric make them eminently post-colonial. What these

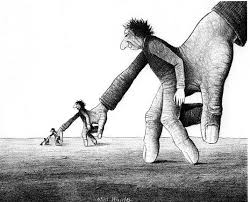

individuals forget however, is that because of Portugal’s unique position in

the global hierarchy, its forms of possible neo-colonialism will be different

from that of other stronger European countries. Thus there is no point

indicating that Portugal has no economic or military capacity or desire to

engage in colonial takeovers today. This fact is painfully obvious. What is

offensively colonial however is the contemporary equivalence that these

particular Portuguese seek with other former colonial powers. This attempt at

equivalence translates into the imitation of the Commonwealth and Francophonie,

in their rejection of post-colonial actions because ‘the British are not asked

to do this’, or in the equally horrific suggestions of their current interest

only in business (economic diplomacy) and not cultural relations.

Colonialism is not only in the

past, it exists in the contemporary when we attempt to create structures of

inequality, rather than equality. The facile rejection of the existence of

these possibilities leads us up the road of possible neo-colonialism.

(A version of this post first appeared in the O Heraldo 25 Dec 2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment