This column on an earlier

occasion remarked on the absolute frustration with the lethargy, cynicism and

callousness that marked the Kamat model of governance that gave the current

government its lease of life. With the election of the Parrikar government

there has also been unleashed, as a result of the same frustration, a variety

of utopian initatives, not least of which is perhaps the Non Motorized Zone

(NoMoZo). This column will deal with two other expressions of this utopian

drive, both of which are, like the NoMoZo, concerned with urban design, and the

experience of life within the city. The first of these expressions is the

suggestions contained in the O Heraldo column of Daniel F. De Souza on the

twenty-fourth of May, and the second, a

YouTube video petition articulated by Joegoauk

Goa, an anonymous visual archivist.

De Souza begins his column by

pointing to some of the very real traffic problems that plague the city of

Vasco da Gama. He points to the disregard for parking rules that see

two-wheelers using space reserved for four-wheelers, and to the unsettling

tendency to overtake from the left. It seems however that De Souza saves his

best ire for last, when he takes on the presence of roadside garages and

makeshift repair shops on the streets of Vasco, charging them with not only

being eye-sores but also with posing an inconvenience and hardship to the

general public. De Souza argues that by conducting their business on the

sidewalk, these shops are forcing the pedestrians off of their rightful space

on the footpaths and onto the road and the path of the disorderly traffic and

endangering the lives of these pedestrians.

The

video petition of Joegoauk

has a similar problem with persons that make a living on the sidewalks and by

the sides of roads. His video draws the attention of the Panjim Municipal

Corporation the Chief Minister (also MLA of the city of Panjim) to the number

of hawkers vending everything from fish, vegetables and plastic toys, amidst

the buses and commuters at the Kadamba bus terminus in Panjim.

Both these interventions in the

public sphere are motivated by a similar logic, suggesting that the roads are

for traffic, the side-walks for the pedestrians, and that the hawkers and

vendors, and others making their livelihood off the streets ought to find some

other place. Indeed, this is the suggestion that De Souza makes at the end of

his column, indicating that the Mormugao Municipal Council ought to identify a

location, and then relocate all the makeshift repair shops to that one single

location. In making this suggestion De Souza is treading on a well-used path, given

that this was a logic that was used in the relocation of the

gadey from various parts of Panjim to

one single location.

Before differing with the logic

that both these gentlemen propose, it should be acknowledged that De Souza does

have a point with problematizing the existence of the vehicle repair shops/

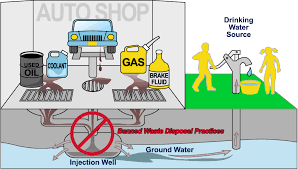

garages, though his logic differs from mine. It is true that these enterprises

do interfere with the use of the sidewalk. However, the larger problem is that

because their presence is not accounted for by the urban-planners or

city-council, the highly toxic waste that they generate is unsuitably handled.

Invariably the oils and grease they reject stain the ground and find their way

into ground water and other water bodies, and other material waste fails to

find a route for appropriate waste disposal. The most significant problem with

these garages is that they externalize the costs of our usage of vehicles,

since the environmental damage that is caused by aging vehicles is not

accounted for. Were these garages forced to fulfill norms laid out by the State

and municipal bodies, the cost for these norms would have to be borne by the

owners of vehicles, giving us a sense of the real cost of our usage of private

vehicles that currently dominate our streets.

For all his good intentions

however, De Souza’s logic does not seem environmentally responsible. On the contrary,

it appears that his logic, and that of Joegoauk, would in fact eventually result in a greater

usage of vehicles and the associated environmental resources. In arguing for

clearing the streets of street-side vendors, both these individuals subscribe

to an urban-planning logic that has created the suburb in other parts of the

world. This logic designs urban spaces by their usage, segregating shopping,

business, residence from each other, and forcing people to use motorized

transport to move from one location to another. Where there is no system of public

transport, this results in high use of private vehicles. Simultaneously this

same logic designates the street for vehicles able to move at high speeds, and

sidewalks for pedestrians only.

There are many problems with this

form of urban design, most significant of which is that it does not correspond

with the realities of life in India. This reality is one that includes a

history of densely populated, multi-use living spaces, as well as the poverty

and markedly unequal distribution of wealth. Urban design models that segregate

urban use from each other, assume the existence of a prosperous, and middle-class

inclined toward high consumption. In forcing the use of private vehicles, this

model also spells the death of integrated communities, creating the conditions

for crime and social dysfunction.

Both De Souza and Joegoauk,

probably have cities like Dubai and Singapore as their models for what our

cities should look like. This is not an uncommon desire among the Indian (and

Goan) middle-class. We should however keep in mind the words of the

RahulMehrotra, and architect, urban studies academic and practitioner who recently

authored “Architecture in India Since 1990.” In a

recent interview he pointed

out that “Looking at Dubai or Shanghai or Singapore as metaphors not only

undermines the fact that we’re a democracy but it also undermines the fact that

the poor even exist in our cities.”

Street-side garages and vendors

exist in our cities not because we are an indisciplined nation, but because

these are forms of urban life and commerce particularly suited to the manner in

which our society is currently socially and economically structured. These

vendors are those who cannot set up shops, and they cater to those who cannot

or are unable to visit shops in the course of their daily life. Having a

vendor, whose prices do not include a substantial overhead makes economic sense

for these consumers. Indeed these vendors are making our society more

productive and efficient, and exist only because there is a need for them.

Rather than hounding these vendors

away from the streets therefore, rather than criminalizing their presence, there

is a need to see how we can effectively integrate them into urban design. De

Souza hits the nail bang on the head when he asks the municipal body to address

these issues, stressing that the general public needs these services. However,

we should be clear that the presence of street vendors is not a problem, that

our cities and roads should be seen as spaces shared by pedestrians and

vehicles and that urban models designed for undemocratic, wasteful societies

are not blindly implemented to our collective loss.

(A version of this post was first published in the Gomantak Times 30 May 2012)

2 comments:

Very good mind opener. if appropriately placed and spaced gaddas can humanise the city scape.

Recently I was surprised to see a fruitseller vanish from a corner near the Muncipal garden( behind the BSNL office ) and near him comes a gadda selling street food.What norms come into paay when these decisins are made ? Fruit gaddas do not cause litter unlike stret food carts which then need disposal systems which I did not see.

Thank you Siren for your comment, and your observation.

I noticed that the street food carts in Miramar do in fact have little bins that cater to the waste that they generate.

I am not sure if the customers use these bins actively, but I do know that the 'helpers' attached to each cart do deal with this waste as a part of their job.

Post a Comment