If you were a

student, living in the mid 2000s in Oñate, a mountain town of the Basque

country, then your entry into San Sebastián would be via train. As you pulled

into the station, and then subsequently headed out of the station into the city

you would pause for a moment. Was there not a faint resemblance to Panjim city?

Did it not feel as if the train station was located where the Patto development

now is? Did the bridges across the Rua do Ourem not correspond to the bridges

across San Sebastián’s Urumea river?

If you were a

student, living in the mid 2000s in Oñate, a mountain town of the Basque

country, then your entry into San Sebastián would be via train. As you pulled

into the station, and then subsequently headed out of the station into the city

you would pause for a moment. Was there not a faint resemblance to Panjim city?

Did it not feel as if the train station was located where the Patto development

now is? Did the bridges across the Rua do Ourem not correspond to the bridges

across San Sebastián’s Urumea river?

The resemblance

of Panjim to this Basque city can be quite confounding. Not only do both cities

lie at the mouths of rivers, but they both also encompass a stretch of beach

that is actively used by its denizens for recreation. Add to these coincidences

the Miramar palace that sits above the city’s famous beach, echoing Panjim’s

own Miramar. Like Panjim, the city too is marked by a number of elegant

promenade spaces. This latter feature however, dates back to the royal

patronage that it enjoyed in the not too distant past, laying the basis for

much that is spectacular in the city.

What makes San

Sebastián truly breath-taking however is not the drama of its geographical

location, a combination of being encircles by beach, river, sea and hills.

Neither is it the food; Basque tapas (pintxos)

are arguably the finest in Spain. Nor is it the spectacular architecture

that constitutes a good amount of the centre of the city. What makes the city

breath-taking is when you realise that a good amount of effort and energy has

gone into making the city accessible to users of non-motorized vehicles. It is

perhaps this reaching out in multiple senses that makes this city all the more

enjoyable.

What makes San

Sebastián truly breath-taking however is not the drama of its geographical

location, a combination of being encircles by beach, river, sea and hills.

Neither is it the food; Basque tapas (pintxos)

are arguably the finest in Spain. Nor is it the spectacular architecture

that constitutes a good amount of the centre of the city. What makes the city

breath-taking is when you realise that a good amount of effort and energy has

gone into making the city accessible to users of non-motorized vehicles. It is

perhaps this reaching out in multiple senses that makes this city all the more

enjoyable.  It is, however,

more than spatial features that create the sense of similarity between these

two widely separated towns. Indeed, both San Sebastián and Panjim share an

uneasy relationship with the country within which they are today located. If

Goa superficially rests easy within the embrace of Mother India, then the same

need not necessarily be said for San Sebastián. Part of the restive Basque

country (Euskal Herria), one could,

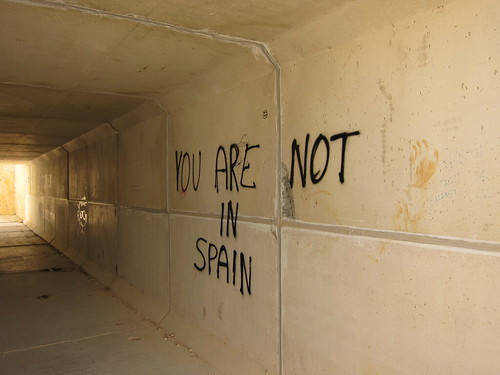

in the period of this itinerant’s visit, find much graffiti on the streets that

testified that not all Basques thought themselves Spanish. Slogans like “Gora Euskadi” cheered on a sense of a

distinct Basque identity, while other slogans (Euskal Presoak Euskal Herrira) dragged ones attention to the

fact that all too often political prisoners were incarcerated outside of the

Basque country, so as to make visits by their families a complicated affair.

It is, however,

more than spatial features that create the sense of similarity between these

two widely separated towns. Indeed, both San Sebastián and Panjim share an

uneasy relationship with the country within which they are today located. If

Goa superficially rests easy within the embrace of Mother India, then the same

need not necessarily be said for San Sebastián. Part of the restive Basque

country (Euskal Herria), one could,

in the period of this itinerant’s visit, find much graffiti on the streets that

testified that not all Basques thought themselves Spanish. Slogans like “Gora Euskadi” cheered on a sense of a

distinct Basque identity, while other slogans (Euskal Presoak Euskal Herrira) dragged ones attention to the

fact that all too often political prisoners were incarcerated outside of the

Basque country, so as to make visits by their families a complicated affair.  Another feature

that both San Sebastián and Panjim share is that they both enjoy more than one

name. San Sebastián also has a Basque (Euskera) name Donostia, while Goa’s

capital is known as Panjim in English, Ponnje in Konkani, and Pangim in

Portuguese. What perhaps distinguishes San Sebastián from Panjim, is that the

former city, following a feature common in the rest of the Basque country,

provides space for both versions of the name. This usage is a result of Spain’s

efforts to accommodate a variety of regional identities, and indeed

nationalisms into the idea of the Spanish nation-state. Now here is something

that one would want to see replicated in Goa! This replication would make sense

given that in recent days there has been some talk of sharpening the similarity between the two cities. If this is a project that is to be taken seriously,

then this is not a project that should end with physical infrastructure. On the

contrary, this is a project that must include an agenda that will balance the

skewed directions of Goa, and Panjim’s cultural policy.

Another feature

that both San Sebastián and Panjim share is that they both enjoy more than one

name. San Sebastián also has a Basque (Euskera) name Donostia, while Goa’s

capital is known as Panjim in English, Ponnje in Konkani, and Pangim in

Portuguese. What perhaps distinguishes San Sebastián from Panjim, is that the

former city, following a feature common in the rest of the Basque country,

provides space for both versions of the name. This usage is a result of Spain’s

efforts to accommodate a variety of regional identities, and indeed

nationalisms into the idea of the Spanish nation-state. Now here is something

that one would want to see replicated in Goa! This replication would make sense

given that in recent days there has been some talk of sharpening the similarity between the two cities. If this is a project that is to be taken seriously,

then this is not a project that should end with physical infrastructure. On the

contrary, this is a project that must include an agenda that will balance the

skewed directions of Goa, and Panjim’s cultural policy.

(A version of this post was first published in The Goan on 23 March 2013)