Like thousands

of middle class and urban persons of my generation who loved to read, my

childhood was marked by a devouring of literature in the English language. Especially through the works of Enid Blyto, I became familiar with the cultural worlds of the English. However, I also had access to the illustrated stories of Amar Chitra Katha.

Through the tales of this publishing house I grew up to know the many

narratives that populate the Puranas, the Hindu epics, and various episodes

from subcontinental history. This reading grew in importance as I began to pick

up on the subtle nationalist messages that form part of growing up in India.

The message was that it was important to know our fables, stories and histories, not merely those from across the

waters.

Like thousands

of middle class and urban persons of my generation who loved to read, my

childhood was marked by a devouring of literature in the English language. Especially through the works of Enid Blyto, I became familiar with the cultural worlds of the English. However, I also had access to the illustrated stories of Amar Chitra Katha.

Through the tales of this publishing house I grew up to know the many

narratives that populate the Puranas, the Hindu epics, and various episodes

from subcontinental history. This reading grew in importance as I began to pick

up on the subtle nationalist messages that form part of growing up in India.

The message was that it was important to know our fables, stories and histories, not merely those from across the

waters.

As I grew older, however, I realised that my knowledge of our narratives was rather curiously limited. While I could easily rattle off the genealogies of the Raghu Vamsha I did not have as deep a knowledge of similar religious traditions within the subcontinent. In time I realised that this was not a coincidence but a part of the way in which Indian nationalism is configured. Religious traditions of brahmanical Hinduism are constructed as national mythology, while other narratives and mythologies are cast as foreign. This is the basis of what one could call banal Hindutva.

For those who fear it, Hindutva is largely associated with the violence, whether it is overt violence, or violent posturing or assertion. This is just one part of Hindutva, however. Violent Hindutva is able to succeed and be condoned largely because it rests on the daily operation of banal Hindutva. This Hindutva ensures that by and large our references are from within the oeuvre of brahmanical tradition, or Indian nationalist interpretations of cultural traditions within the subcontinent. By depriving us of other referents, it is as if this Hindutva casts a spell where we are unable to imagine ways to challenge its operation.

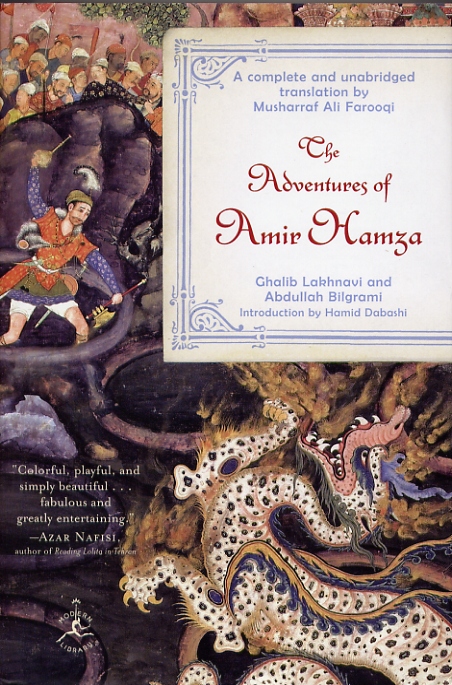

On realising this I figured that one route to challenging the operation of banal Hindutva would rest on uncovering and popularising subcontinental narratives from outside the brahmanical tradition. One obvious place to go searching for these narratives was the subcontinent’s Islamicate tradition. From within this tradition, I ran into the Dastan e Amir Hamza a number of times, the first of which was a short version of the tale published by the Khudha Baksh Oriental Library. More recently, I had the opportunity to go through a more substantial translation of the text by Musharraf Ali Farooqi.

The dastan, or tale, is woven around the fantastic adventures of Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad. In the course of his travels across a broad swathe of the globe, as well as other dimensions, Hamza battles kings in their kingdoms, sorcerers and their spells (tilism) and other supernatural creatures. While Hamza often converts noble adversaries to Islam after defeating them, the narrative itself is not a theological or religious discourse. Indeed, decorated with tales of magic, romance and cunning, I am given to believe that more pedantic Muslims would shirk away from the narrative as un-Islamic.

If the intention of exploring Islamicate wonderlands is to expose the Indian reader to a wider cultural landscape, then the dastan is a wonderful choice. I was delighted by the sheer geographic scale of the narrative, that casually incorporates Hind (the subcontinent of south Asia), Ceylon, Persia, Greece, China into the narrative. In many ways the dastan is true to Indian tradition in that it makes unselfconscious references to Alexander exploits. While Alexander may have reached the limits of his adventures in the Punjab, his exploits fundamentally reordered the cultural universe of the world from that time. While the Persian empire was already a standard that even subcontinental monarchs looked up to, Alexander’s incursions made the cultural references of the subcontinent even more complex. That contemporary Indians are ignorant of these complex cultures is testament to the manner in which banal Hindutva has stripped our world of cultural diversity. A further testament to the Dastan’s richness is the manner in which narratives that one finds in the Ramayana, such as Rama’s breaking of Parashurama’s bow, also seem to emerge, albeit under modified circumstances, in the same text.

As interesting as the Dastan may be, however, and even though in recent times there has been a rediscovery of the subcontinent’s dastan tradition, it is not ready for uncritical embrace. Merely because it is Islamicate is not going to allow the dastan to challenge Hindutva or be an acceptable alternative. The dastan as it now stands is filled with a variety of racist, patriarchal and casteist formulations. Take, for example, the manner in which Hamza’s companion and friend from birth, Amar, is constantly humiliated because of the latter’s low birth. Further, it appears that it is only figures of “low birth” who engage in morally dubious activities, even if it is to further Hamza’s noble pursuits. Or the instances where Hamza is persuaded to enjoy the charms of other women, while his first love, Mehr Nigar, pines chastely for him for decades.

But perhaps it is because there is much that needs to be weeded out of the Dastan that it may present itself as an interesting and exciting task in the battle against banal Hindutva. Hindutva is not the only ideology in the country that rests of a thick melange of racism, patriarchy, casteism and other dehumanising systems. As local readers would know these systems are as present within the institutional Church in Goa, as they are in other religious and secular institutions. All of these institutions work with banal Hindutva on a daily basis, by and large protesting only when violent Hindutva pinches their immediate interests. Reformulating the Dastan, and other narratives, both from within the subcontinent as well as outside, would perhaps present a more dynamic challenge in reinventing the country to make it more inclusive. And who knows, in challenging the sorcerers that would modify the secular democratic republic into the tilism of Hindutva, we may well stand to become the Hamza of our age.

(A version of this post was first published in the O Heraldo on 3 Oct 2014)

No comments:

Post a Comment