I remember the first time I arrived in

Lisbon. I had imagined that I would find the city unfamiliar, filled with

strangers. This was true to a large extent, and yet, the city endeared itself to me by offering me encounters with persons from my childhood.

It was an overwhelming experience to encounter the people like Afonso de

Albuquerque, Vasco da Gama, persons whose names I had first encountered as a boy.

Of course these men were long dead, but their memorialised presence still

lurked in the city, making the city at once familiar.

I remember the first time I arrived in

Lisbon. I had imagined that I would find the city unfamiliar, filled with

strangers. This was true to a large extent, and yet, the city endeared itself to me by offering me encounters with persons from my childhood.

It was an overwhelming experience to encounter the people like Afonso de

Albuquerque, Vasco da Gama, persons whose names I had first encountered as a boy.

Of course these men were long dead, but their memorialised presence still

lurked in the city, making the city at once familiar. I had a similar experience when visiting

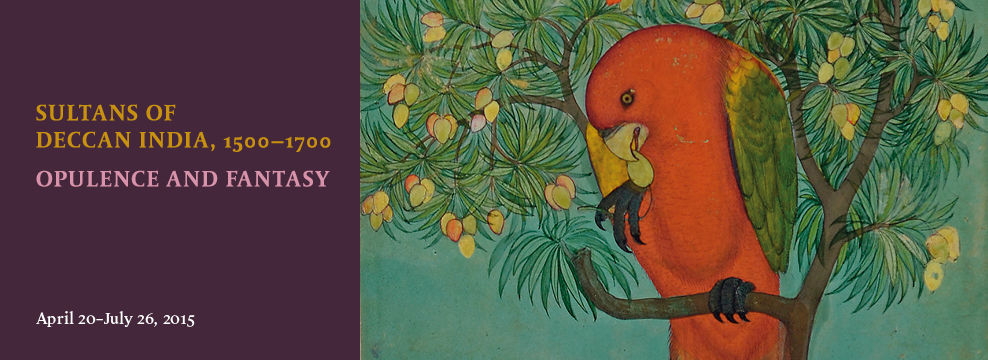

the ongoing exhibition titled “Sultans

of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy”, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

in New York. Dedicated to delineating the often ignored history, and material

productions of the various sultanates of the Deccan, the exhibition brought me

face-to face with persons whose histories are intertwined with those of the

early modern Portuguese in South Asia. I jumped with particular delight at the

portraits of various members of the Adil Shahi dynasty.

I had a similar experience when visiting

the ongoing exhibition titled “Sultans

of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy”, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

in New York. Dedicated to delineating the often ignored history, and material

productions of the various sultanates of the Deccan, the exhibition brought me

face-to face with persons whose histories are intertwined with those of the

early modern Portuguese in South Asia. I jumped with particular delight at the

portraits of various members of the Adil Shahi dynasty.

Just as the names of the great heroes of

the Portuguese expansion are known to most Goans, so too, even the most cursory

reading of Goan history will make one aware of at least one figure of Deccan history,

Sultan Yusuf Adil Shah, the founder of the dynasty. Indeed, the old Secretariat

of the Government of Goa, was housed in the building that was, and continues to

be called the Palácio do Idalcão - the palace of Adil Shah.

Many assume that the significance of the Adil Shahis in Goa's history is concluded once the territory was conquered by the early modern Portuguese. As such, we often do not bother with this Deccan sultanate. Goa’s association with the Adil Shahis of Bijapur was more than a mere footnote, however. The Portuguese Estado da India would have substantial dealings with the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur. It was with this Sultanate that treaties were signed that allowed Ilhas, Bardez and Salcete to form the core of the territory that would in later times become known as Goa. And for the longest time the Estado lived in the shadow of the Bijapuri sultanate. As the historian David Kowal, and the late José Pereira had indicated, so strong was the influence of the Bijapuris, that the architecture of Goa began to mimic aspects of Bijapuri architecture. This influence can especially be seen in the lamp towers of the older temples in Goa, as well as in the faceted bell towers of churches across Goa.

However, it was not just in the

architecture of the Old Conquests of Ilhas, Bardez and Salcete that there was a

Bijapuri influence. Portions of what would come to be called the New Conquests

continued to be a part of the Bijapuri Sultanate until they were integrated

into the Estado da Índia. It is to the Indo-Persian administrative organisation

followed by the Bijapur sultanate that we owe the identity of such identities

as that of Antruz Mahal. Further, the Christian history of the New Conquests

owes as much to the Bijapuri Sultanate as it may to the Portuguese state. It

was under leave from the Sultan, in about 1639, that Mateus de Castro, the

ambitious native cleric who chafed under the Portuguese, received permission to

build churches in Bicholim, Banda, and Vengurla.

Unfortunately for us, the exhibit at The

Metropolitan museum does not contain an individual and contemporary portrait of

the founder of the dynasty Yusuf Adil Shah. We are forced to satisfy ourselves

with a reference to this man in a group portrait depicting the entire dynasty.

Another portrait that might attract Goan interest was one which depicts two

persons in attendance on the Sultan Ali Adil Shah II. The audio guide to the

exhibit suggests that these two persons are said to be Shivaji and his father,

Shahaji Bhonsle. It should not be forgotten that Shahaji held an official rank

in the Adil Shahi army, and it was from the Adil Shahi sultanate that Shivaj

forged the nucleus of his kingdom.

Unfortunately for us, the exhibit at The

Metropolitan museum does not contain an individual and contemporary portrait of

the founder of the dynasty Yusuf Adil Shah. We are forced to satisfy ourselves

with a reference to this man in a group portrait depicting the entire dynasty.

Another portrait that might attract Goan interest was one which depicts two

persons in attendance on the Sultan Ali Adil Shah II. The audio guide to the

exhibit suggests that these two persons are said to be Shivaji and his father,

Shahaji Bhonsle. It should not be forgotten that Shahaji held an official rank

in the Adil Shahi army, and it was from the Adil Shahi sultanate that Shivaj

forged the nucleus of his kingdom. The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum

was not limited to just the Bijapuri Sultanate. It focused on the huge amount

of cultural production that emerged from the various other Sultanates,

including that of Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Golkonda. In doing so the exhibition

suggests at the wide variety of influences that bore upon the medieval and

early modern Deccan, and have come to bear on our own contemporary culture.

Indeed, while browsing through the exhibit, I wondered if it would not be a

good idea were an exhibition curated to look exclusively at the Bijapuri

sultanate. The state of Goa is intimately linked to this sultanate and it would

do us good to appreciate the intimate links that existed between the Sultanate

and the Goa that was being formed. To that extent, Bijapuri history is as much

Goan history, as is the history of the Portuguese state whether in South Asia

or in Europe. It would also be a particularly moving homecoming were such an

exhibition housed in the now vacant Palácio do Idalcão.

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum

was not limited to just the Bijapuri Sultanate. It focused on the huge amount

of cultural production that emerged from the various other Sultanates,

including that of Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Golkonda. In doing so the exhibition

suggests at the wide variety of influences that bore upon the medieval and

early modern Deccan, and have come to bear on our own contemporary culture.

Indeed, while browsing through the exhibit, I wondered if it would not be a

good idea were an exhibition curated to look exclusively at the Bijapuri

sultanate. The state of Goa is intimately linked to this sultanate and it would

do us good to appreciate the intimate links that existed between the Sultanate

and the Goa that was being formed. To that extent, Bijapuri history is as much

Goan history, as is the history of the Portuguese state whether in South Asia

or in Europe. It would also be a particularly moving homecoming were such an

exhibition housed in the now vacant Palácio do Idalcão.

The discussion of Goa is often framed

between two tropes: that of Goa Dourada, or Goa Indica. The first, seeks to

emphasize Goa’s European, or Portuguese-ness. In response to this first form of

representation, the second attempts to stress that Goa is, in fact, Indian. While

there is no denying that Goa does constitute a certain form of Europe, this

second form is also important. The trouble with Goa Indica, however, is that it

often stresses a Sanskritic and brahmanical past for Goa. These assertions are

then used to justify

a return to that imagined state of affairs. The truth, as always, is

perhaps somewhere in between. The areas that became Goa had a complex past with

multiple influences. If these territories were influenced by the Vijayanagara

polity, then the kings of Vijayanagara themselves adopted an Islamicate model

of kingship calling

themselves Sultans. If Bijapur was a significant centre through which

Shia Islam permeated the lore of the indigenous deities of the Deccan like Yellamma

and Parashurama, then the Sultans and their courts adopted Indic forms of

asserting their kingship. We need more histories that assert to this

complexity, and communicate this to a larger, increasingly misled, popular audience. It is towards these histories that exhibitions such as the Sultans of the Deccan could lead us.

(A version of this post was first published in the O Heraldo dated 26 June 2015)

1 comment:

Agree wholeheartedly with this article. Our history is presented in such an oversimplified manner that it is too easy to see our identities in black or white. I have not seen the Adil Shahi dynasty feature in history lessons in any school syllabus that I know of even in Karnataka !!

Lovely post.

Post a Comment