My earlier

responses to Fonseca did not follow from a consideration of his work, but were

largely a response to the project of inculturation he was committed to. Since

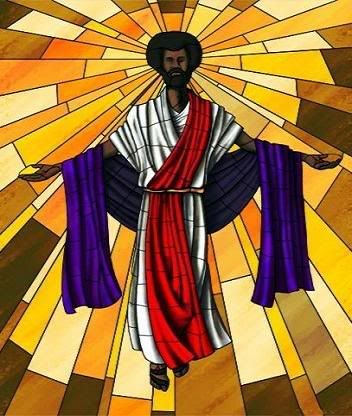

even before the 1960s and the dramatic changes of the Vatican Council II, there

had been a movement to depict Christ, his mother and the Saints in forms that

were not restricted to Aryan stereotypes. There was a clamour in some sectors

to depict the universal Christ in universal tones. People wanted to see Christ

not merely as a blond blue eyed man, but in darker skin tones, outside of

northern European locales.

My earlier

responses to Fonseca did not follow from a consideration of his work, but were

largely a response to the project of inculturation he was committed to. Since

even before the 1960s and the dramatic changes of the Vatican Council II, there

had been a movement to depict Christ, his mother and the Saints in forms that

were not restricted to Aryan stereotypes. There was a clamour in some sectors

to depict the universal Christ in universal tones. People wanted to see Christ

not merely as a blond blue eyed man, but in darker skin tones, outside of

northern European locales. In itself this was not a bad idea. After all, Christ emerged from out of Palestine, the likelihood of his being blond and blue eyed are slim. The problem with the project of inculturation, however, was that in South Asia, this project became a project of brahmanising Christ. Christ and his story were depicted within forms that one can relate directly to brahmanical Hinduism. It is as if Christ lived within an entirely Hindu upper-caste milieu. Such a project has a number of problems, first it devalues the natal culture of many Christians. Born from the encounter of Europe with subcontinental South Asia, these Christians have internalised many European forms that have become local. Further, representing Christ in brahmanical forms perpetuates a casteism that is arguably not a part of the Christian message.

Viewing the art works on display at the XCHR my usual irritation was displaced by an amazement for the details I saw in Fonseca’s art. Take, for example, the little squiggle at the end of a line that he uses to represent the Holy Spirit in his representation of the Annunciation. Or the very realistic little lilies in another image.

Even if one disliked the brahmanical references, one had to appreciate the clever way in which Fonseca interpreted these forms. For example, traditional European depictions of Saint Anne often have her seated while instructing her daughter Mary. Fonseca takes this form but instead uses the Shiva-Shakti model, where a miniature Shakti sits on the left thigh of Shiva. Brilliant!

One of the

problems with Indian nationalism is that it casts the woman as the bearer of

the national image. Thus, she is expected to be demure, always in a sari, and

her pallu draped decorously over her

head. Some of this odious nationalism emerges in Fonseca’s art. The grief of

Mary as she wails either at the foot of the cross, or with her dead son in her arms

is a spectacular feature in Western art. None of this sort of anguish is

visible in many of Fonseca’s depictions of Mary at the scene of and after the

crucifixion. And it is not as if real south Asian women do not make dramatic,

heart-rending spectacles of their grief. The nationalist image of the woman,

even when suffering, is of a demure little thing. This is where one regrets

Fonseca’s nationalist inspiration.

One of the

problems with Indian nationalism is that it casts the woman as the bearer of

the national image. Thus, she is expected to be demure, always in a sari, and

her pallu draped decorously over her

head. Some of this odious nationalism emerges in Fonseca’s art. The grief of

Mary as she wails either at the foot of the cross, or with her dead son in her arms

is a spectacular feature in Western art. None of this sort of anguish is

visible in many of Fonseca’s depictions of Mary at the scene of and after the

crucifixion. And it is not as if real south Asian women do not make dramatic,

heart-rending spectacles of their grief. The nationalist image of the woman,

even when suffering, is of a demure little thing. This is where one regrets

Fonseca’s nationalist inspiration. Similarly, there

is a little bank of photographic images of Fonseca, sometimes with family.

These are left marooned in a sea of his art works, leaving us no way in which

to engage with them. These images could have been the subject of an independent

exhibition, or juxtaposed to demonstrate, as an artist friend pointed out to

me, how the face of Fonseca’s Madonna’s often resembles that of his wife.

Similarly, there

is a little bank of photographic images of Fonseca, sometimes with family.

These are left marooned in a sea of his art works, leaving us no way in which

to engage with them. These images could have been the subject of an independent

exhibition, or juxtaposed to demonstrate, as an artist friend pointed out to

me, how the face of Fonseca’s Madonna’s often resembles that of his wife. Regardless of

these small shortcomings, The ‘Angelo da Fonseca RETROSPECTIVE’ is an

exhibition worth visiting. What is heartening is that the XCHR also provides

prints of some of Fonseca’s works available for purchase. One wishes this

little initiative well because it bears the seed of great promise, allowing

Fonseca’s images to be spread wider afield, entering homes as objects of veneration,

supplementing the existing bank of Aryan Christs that rule the roost today.

Regardless of

these small shortcomings, The ‘Angelo da Fonseca RETROSPECTIVE’ is an

exhibition worth visiting. What is heartening is that the XCHR also provides

prints of some of Fonseca’s works available for purchase. One wishes this

little initiative well because it bears the seed of great promise, allowing

Fonseca’s images to be spread wider afield, entering homes as objects of veneration,

supplementing the existing bank of Aryan Christs that rule the roost today.