Goa

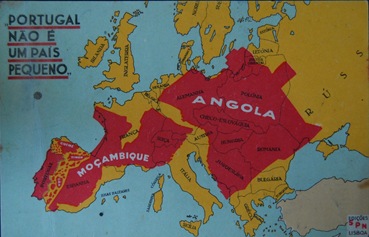

não é um país pequeno, if translated, quite literally would read as “Goa is not a small

country.” The title for this exhibition has been borrowed from a similar phrase

that was articulated by the New State (Estado

Novo), the authoritarian regime that ran Portugal from the 1930s to 1974. The

start of the twentieth century was not easy for the Portuguese state. It faced

challenges from other European colonial powers, saw the collapse of the

monarchy, and the start of a shaky Republic. The New State that emerged in the

1930s promised an end to all of this instability. In the face of challenges

from other European powers and the rising tide of anti-colonial nationalist

movements, the New State asserted that Portugal was not a small peripheral European country but a great multiracial nation. The New

State argued that the various territories that Portugal held across the world

were not colonies but in fact overseas provinces of the country. It was, in

sum, one vast multi-continental country. It was in this context that the New

State articulated the slogan Portugal

não é um país pequeno—Portugal is not a small country—and refused to countenance any

suggestion of freedom or autonomy for its colonies. Goa, as is well

known, was a Portuguese possession until 1961, the year that the Republic of

India subsumed the territory into itself. In the final analysis, it was

this metropolitan intransigence embodied by Portugal não é um país pequeno that was, to a great extent, responsible for the troubled manner in

which Goa was integrated into the Republic of India.

Goa

não é um país pequeno, if translated, quite literally would read as “Goa is not a small

country.” The title for this exhibition has been borrowed from a similar phrase

that was articulated by the New State (Estado

Novo), the authoritarian regime that ran Portugal from the 1930s to 1974. The

start of the twentieth century was not easy for the Portuguese state. It faced

challenges from other European colonial powers, saw the collapse of the

monarchy, and the start of a shaky Republic. The New State that emerged in the

1930s promised an end to all of this instability. In the face of challenges

from other European powers and the rising tide of anti-colonial nationalist

movements, the New State asserted that Portugal was not a small peripheral European country but a great multiracial nation. The New

State argued that the various territories that Portugal held across the world

were not colonies but in fact overseas provinces of the country. It was, in

sum, one vast multi-continental country. It was in this context that the New

State articulated the slogan Portugal

não é um país pequeno—Portugal is not a small country—and refused to countenance any

suggestion of freedom or autonomy for its colonies. Goa, as is well

known, was a Portuguese possession until 1961, the year that the Republic of

India subsumed the territory into itself. In the final analysis, it was

this metropolitan intransigence embodied by Portugal não é um país pequeno that was, to a great extent, responsible for the troubled manner in

which Goa was integrated into the Republic of India.

In the context of the present exhibition, this imperialist phrase is

reutilized to suggest that Goa’s small geographical extent does not limit its

size. Despite the fact that Goa is the smallest territory in the Union of

India, it is home to a remarkably diverse history. Not only does it play host

to a variety of migrant communities; it is also the home of a migrant community

that is spread across the world. As the artworks in this exhibition

demonstrate, and this essay elaborates, this breadth of experience allows for

Goans to hold a variety of perspectives and to own diverse insights into the

multiple worlds that they occupy.

The structuring concerns

If there is one intention that guides this

exhibition, then it is the desire to represent the breadth and diversity of the

Goan experience through art. This desire is in fact the result of a number of

concerns that the curator, Viraj Naik, encountered when charged with putting together

the exhibition. The concerns that he encountered are not necessarily personal

but those that bother many Goans.

Foremost of the questions that agitate many Goan minds is the issue of

identity. Way back in 2005, the art scene in Goa faced a peculiar situation

when Pedro Adão, the Consul of Portugal in Goa of the time, organised a show titled

“Portugal through the eyes of artists in Goa” [emphasis added]. This formulation was the result of identitarian conflicts

within Goa, where some native Goan artists asserted that only they could claim

to be Goan artists. Those who were not sons of the soil, the logic went, could not

call themselves Goan artists; they were merely artists in Goa. It is perhaps in response to these identitarian

politics that the artists presented in this exhibition include persons who

could be called native Goans as well as those who, though not native to the

territory, have made Goa their home for generations now. The exhibition

includes both Goans based in Goa and those who have settled outside of Goa. The

ensuing selection of artists was also determined in an attempt to represent

experience, allowing us to see the work of those who are well-established, mid-career

practitioners, and younger artists.

The diversity that this exhibition has attempted to reflect has also

ensured, perhaps inadvertently, that this selection of artists represents a

number of bahujan voices. This is truly a positive step in the

representation of artistic work from Goa. Until recently, the more celebrated

of Goa’s artists, such as Mario Miranda, Angelo da Fonseca, Francis N. Souza,

Ganesh Vamona Navelcar, and Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, have all hailed from dominant

caste backgrounds. That this unilateral representation will give way to art

from a range of social locations will only add richness to the way in which Goa

is figured and read.

The diversity that this exhibition has attempted to reflect has also

ensured, perhaps inadvertently, that this selection of artists represents a

number of bahujan voices. This is truly a positive step in the

representation of artistic work from Goa. Until recently, the more celebrated

of Goa’s artists, such as Mario Miranda, Angelo da Fonseca, Francis N. Souza,

Ganesh Vamona Navelcar, and Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, have all hailed from dominant

caste backgrounds. That this unilateral representation will give way to art

from a range of social locations will only add richness to the way in which Goa

is figured and read.

Another concern that plagues the Goan is the sense of being ignored and

being left on the sidelines, be it nationally or indeed within Goa itself. It

was Viraj’s opinion that the visual art that emerges from Goa is too often not

given adequate attention even within Goa itself. His attempt, therefore, was to

create a space for the various aspects of the visual by representing, in

addition to the traditional categories, those of photography, video and

sculpture.

Above all, the curation of this exhibition was fuelled by the desire of

most Goans to somehow capture Goan-ness. As I will go on to discuss, this

desire to define Goan-ness has emerged from the rapid changes that have

occurred in Goa, not only with its integration into the former British India

but also as a result of the dramatic changes that have taken place within the

territory in recent years, such as the change in local lifestyles due to the departure

from a largely agrarian economy, as well as the dramatic change in demography resultant

from an increased flow of migrants into the territory, not to mention the surge

in floating populations—almost twice the size of the host population—during peak

tourist season. The other concerns that have motivated this desire to define

Goan-ness are the felt need to create a secular vision for Goa, one that rises

above the sectarian identities that plague a community impacted by dramatic and

rapid change. One source for this vision, Viraj believes, is in the production

of artists, who know no religion beyond art. I personally do not share this

conviction about artists being above quotidian concerns and divorced from

politics. This position smacks too much of the romanticist notion of the artist

as standing apart from society. The works of artists are interesting primarily

because they are a part of society and allow us insight into the workings of

the society from which they emerge. As I will go on to demonstrate, however, his

selections have in fact managed to present a bouquet of artworks that can

intervene in and complicate the discourse on Goan identities positively.

Continuity and change

|

| "Past Perfect", Ramdas Gadekar |

That change is a major cause for those associated intimately with

Goa is obvious from the fact that at least three of the contributions to this

exhibition deal with change. Ramdas Gadekar’s twin contributions, “Past

Perfect” and “Future Tense,” respond to the changes in income patterns that

have allowed children to move from the rustic games of Goa’s past that involved

physical exertion to amusing themselves with tablets, mobile phones, and

computer games. What is interesting about Gadekar’s representation of the

perfect past is also the gun and dart shaped “toys” that are used to burst fire

crackers. While most Indians may associate crackers with Diwali, in Goa, it is

the feast of Ganesh Chaturthi that is punctuated by the bursting of fire

crackers—a Goan specificity that most are aware of and marks one more feature

that carves out a distinct Goan identity.

|

| "Memory That Scandalously Lies", Aasmani Kamat |

If Gadekar’s

contributions are redolent of nostalgia for a past that is imagined as perfect,

through her contribution, “Memory that Scandalously Lies,” the

Bangalore based Aasmani Kamat eschews any valorisation of the past. Her concept

note informs us that our memories of the past are invariably embellished by our

present and hence are unreliable. Despite her refusal to indulge in nostalgia,

the works by both Kamat and Gadekar are united by their gaze at childhood. This

is perhaps largely because it is childhood that is the imagined space of purity

and authenticity. That it is the topography of childhood that is obviously

changing is perhaps the reason for Gadekar’s nostalgia.

|

| “A Perilous Leap of Faith”, Krishna Divkar |

Two other works,

though not overtly concerned with change, are engaged with the process of

archiving traditions, some of them continuing, from Goa’s past. Hemant Parab

captures performances of folk dances, while Krishna Divkar’s “A Perilous Leap

of Faith” captures a peculiar tradition among the Catholics in Goa. The feast

of São João, or Saint John the

Baptist, is commemorated on 24 June, a good few weeks after the monsoons would

have hit Goa. At this point in time, the wells are quite literally overflowing,

and Catholics in particular celebrate the feast by wearing crowns of leaves and

flowers, and jumping into these wells. These leaps are a reference not only to

John’s use of water for baptism but also his leap of joy while still in the

womb, when his mother Elizabeth met her cousin Mary, who was then bearing the

future Messiah, Jesus. The image that Divkar captures offers a particular

nuance to this tradition. Children born after an act of divine favour was

requested are also crowned with wreaths and taken into the waters with caring

adults as a thanksgiving for the fulfilment of the favours petitioned.

|

| "War Heads", Assavari Kulkarni |

Assavri Kulkarni’s

photographs have a sculptural quality to them highlighting a natural symmetry.

If there is one single factor that most nostalgic Goans will agree on, it is of

the memory of Goa that was green and linked with nature and natural cycles. Kulkarni’s

images, which also contain the image of fish—possibly the food for which all

Goans share a passion—echo this fascination for the natural.

In her offering

to the exhibition, Rajeshshree Thakkar continues working with the mobile

elements that defined her earlier works. “Prayer Wheel for Goa” seems to make

obvious that given the rapid changes that are overtaking Goa, there is a need

to pray for the land, its people and its traditions. What is left to our

imagination is whether this prayer is one for a peaceful death or one for

sturdy continuity.

|

| "Prayer Wheel for Goa", Rajeshshree Thakkar |

Defining Goan-ness

Predominant in Thakkar’s “Prayer Wheel for Goa” are images of a Goa

that are linked to the Goan, and especially the Catholic elite’s engagement

with the European and Portuguese cultures. To many, these images that craft the

vision of a Goa Portuguesa are

indisputable hallmarks of Goan-ness. And yet the issue of what exactly defines

Goan-ness is a hugely contested battleground. The trope of Goa Portuguesa, or Portuguese Goa, emerged in the twilight years of

Portuguese sovereignty over Goa and as a logical extension of the Portuguese

state policy that Portugal was one indivisible, multi-continental nation.

Goans, the authoritarian Portuguese New State argued, were not Indian, but

profoundly Portuguese. This assertion, strangely enough, got reaffirmed in the

period subsequent to integration into the Indian Republic, and especially under

the years of Congress rule in the 1980s, when it was used to aggressively

market Goa as a Western paradise in India. This image continues to be crudely

imitated by those who wish to sell Goa as a space of leisure, whether for

tourists or middle class and rich Indians seeking holiday homes in Goa.

Predominant in Thakkar’s “Prayer Wheel for Goa” are images of a Goa

that are linked to the Goan, and especially the Catholic elite’s engagement

with the European and Portuguese cultures. To many, these images that craft the

vision of a Goa Portuguesa are

indisputable hallmarks of Goan-ness. And yet the issue of what exactly defines

Goan-ness is a hugely contested battleground. The trope of Goa Portuguesa, or Portuguese Goa, emerged in the twilight years of

Portuguese sovereignty over Goa and as a logical extension of the Portuguese

state policy that Portugal was one indivisible, multi-continental nation.

Goans, the authoritarian Portuguese New State argued, were not Indian, but

profoundly Portuguese. This assertion, strangely enough, got reaffirmed in the

period subsequent to integration into the Indian Republic, and especially under

the years of Congress rule in the 1980s, when it was used to aggressively

market Goa as a Western paradise in India. This image continues to be crudely

imitated by those who wish to sell Goa as a space of leisure, whether for

tourists or middle class and rich Indians seeking holiday homes in Goa.

In opposition to

the idea of a profoundly Portuguese Goa emerged that of Goa Indica. Goa’s identity, the partisans of the latter idea

affirmed, had nothing to do with Portuguese influences, but was deeply

connected with India. If the Portuguese state leaned toward one extreme, the

votaries of Goa Indica swung toward its

polar opposite. Even as Goa’s society changes rapidly, the truth perhaps lies

somewhere in the middle. In any case, rather than attempt to adopt a single

definition, it makes sense to be attentive to the suggestions that emerge from

the ground; in this case, the works on display in this exhibition.

One thing that emerges strikingly in much of the contemporary artistic production from Goa is the figure of Christ or references to what could broadly be called Catholic lifestyles. This exhibition’s collection of artworks is no exception to this rule.

|

| “d

lesson” Shripad Gurav |

|

| "The Third Lie", Pradeep Naik |

|

| Shirgão, Krishna Divkar |

While the protests against the devastating effects of mining have received the support of the Catholic Church, which has maintained a commitment to environmental justice, the heroes of the agitation have sprung from the Adivasi communities of Goa. Is it this face of the contemporary martyr that Pradeep Naik presents against the backdrop of the ravaged land?

Another vaguely

Christ-like figure manifests in Sagar Naik Mule’s sculpture “Armageddon.” The

reference to Christ’s Last Supper is also present in Vitesh Naiks’s cluster of

works. The Christian influence is perhaps more nuanced in the work of Kedar

Dhondu, the title of whose video installation, “Refrain from anger and turn from

wrath, it leads only to evil,” is in fact a quote from a biblical Psalm. His

work is a contemplation on wrath, one of the seven sins, or cardinal vices, as articulated

by Christian ethics. That so many artists engage with these Christian images,

despite their not confessing Catholicism, goes to document the integral part

that the Christian vision plays in moulding a Goan sensibility.

Another vaguely

Christ-like figure manifests in Sagar Naik Mule’s sculpture “Armageddon.” The

reference to Christ’s Last Supper is also present in Vitesh Naiks’s cluster of

works. The Christian influence is perhaps more nuanced in the work of Kedar

Dhondu, the title of whose video installation, “Refrain from anger and turn from

wrath, it leads only to evil,” is in fact a quote from a biblical Psalm. His

work is a contemplation on wrath, one of the seven sins, or cardinal vices, as articulated

by Christian ethics. That so many artists engage with these Christian images,

despite their not confessing Catholicism, goes to document the integral part

that the Christian vision plays in moulding a Goan sensibility. |

| "Apocalypse", Sagar Naik Mule |

This obsession

with hyper-masculinised male torsos is also evident in the popular art that

emerges when Goans celebrate Diwali. The difference of Hinduism in Goa ismarked by the fact that the effective high point of the Diwali celebrations iswhat has come to be called Narakasur Nite. In Goa, the night of Naraka Chaturdashi,

the lunar day before the new moon night when the goddess Laxmi is worshipped,

sees the preparation of effigies of the asura

Naraka. These effigies are the focus for raucous music until the wee hours of

the morning, when the effigy, stuffed with crackers, is consigned to flames. In

recent years, these effigies that earlier depicted the robust body of the asura have given way to depictions from

the torso up. Like the torso that Mule has sculpted, these new avataars of

Naraka are grotesquely muscled. I suspect that it is because of the structural

challenges that this new body type presents that these effigies now focus only

from the torso up and, rather than being constructed entirely of combustible

materials, are now built over a frame of iron girders rooted in concrete bases.

This obsession

with hyper-masculinised male torsos is also evident in the popular art that

emerges when Goans celebrate Diwali. The difference of Hinduism in Goa ismarked by the fact that the effective high point of the Diwali celebrations iswhat has come to be called Narakasur Nite. In Goa, the night of Naraka Chaturdashi,

the lunar day before the new moon night when the goddess Laxmi is worshipped,

sees the preparation of effigies of the asura

Naraka. These effigies are the focus for raucous music until the wee hours of

the morning, when the effigy, stuffed with crackers, is consigned to flames. In

recent years, these effigies that earlier depicted the robust body of the asura have given way to depictions from

the torso up. Like the torso that Mule has sculpted, these new avataars of

Naraka are grotesquely muscled. I suspect that it is because of the structural

challenges that this new body type presents that these effigies now focus only

from the torso up and, rather than being constructed entirely of combustible

materials, are now built over a frame of iron girders rooted in concrete bases. |

| "Rebirth", Santosh Morajkar |

In “Divine

Journey,” Sonia Rodrigues Sabharwal demonstrates the fascination with Hinduism

that animates a number of contemporary Catholics in Goa. While one of the

images offered by Sabharwal is a reworking of the Catholic icon of the flight

of the Holy Family into Egypt, the rest of her images engage with Puranic

deities and Hindu festivity. What is one to make of the squat bodies and flat

noses of these images, however? While this imaging of the human body is

characteristic of a number of Rodrigues’ works, could it also be seen as

stemming from the desire to move away from the vaguely European and Aryan

imaging of the Hindu body, as evidenced by the works of Ravi Varma and subsequent

Hindu imagery?

|

| “Divine Journey,” Sonia Rodrigues Sabharwal |

|

| "The Great Indian Rope Trick" Walter D'Souza |

Goans and the world

|

| "Apparition of Roman head...", Vijai Bhandare |

|

| "Mind's eye", Karl Antao |

|

| "Night Walks- Baroda" Karishma D'Souza |

Continuing conversations

An ideal location to conclude this discussion of the works curated

within this exhibition would be the pictographs titled “Cultural Conversation”

contributed by Viraj Naik. These assemblages present a variety of characters

drawn from a number of his earlier works. Viraj is clear that these characters are

not Goan characters but embody universal aspects. They emerge from different

locales and periods, and seem to be engaged in conversations across diverse

landscapes, some of which, like the river that cuts across both images, one

could identify as distinctly Goan.

| |||

| "Cultural Conversation- 3", Viraj Naik |

Even though the

popular imagination has pegged the sea as the quintessential element of the

Goan landscape, this is perhaps more the result of external imaginations of

Goa. Until recently, except for the fishing communities for whom the sea was

the site of labour, the sea was an alien element to many Goans. It was perhaps only

from the early twentieth century that the Goan middle classes, in imitation of

European fashions of the time, began to vacation by the seaside in the summer

so that they could take the waters. Until this time, the river had possibly

been the landscape feature that defined Goan identities. It was the rivers that

marked boundaries, whether prior to the arrival of the Portuguese or even

subsequent to their arrival. Indeed, in the first phase of Portuguese expansion

from the city of Goa, it was the rivers that provided boundaries for the realms

of the Portuguese Crown. As a fragment in Thakkar’s assemblage indicates, the

Portuguese armadas did not merely sail across the seas; they also sailed up the

rivers to assert their sovereignty over the city of Goa and other ports. Despite

engaging in trade across the seas, these ports were located upstream from the

sea. Until the advent of macadamised roads and petroleum-fuelled automotive

transport, it was the rivers that allowed for rapid transportation across the

various territories that today constitute Goa. It is little wonder, then, that

besides Viraj, the centrality of the river to Goan narratives is echoed by the

Goan poet Manohar Shetty’s collection of Goan short stories, titled Ferry Crossings (2000), while Reflected in Water (2006) is the name of

Jerry Pinto’s collection of writings on Goa. In fact, what is perhaps one of

the most famous conversations from the Goan cultural repertoire, between a

dancing girl and a boat man in the folk song Choltam Choltam, popularly known as hanv saiba poltodi voita, takes place on the bank of a river.

Even though the

popular imagination has pegged the sea as the quintessential element of the

Goan landscape, this is perhaps more the result of external imaginations of

Goa. Until recently, except for the fishing communities for whom the sea was

the site of labour, the sea was an alien element to many Goans. It was perhaps only

from the early twentieth century that the Goan middle classes, in imitation of

European fashions of the time, began to vacation by the seaside in the summer

so that they could take the waters. Until this time, the river had possibly

been the landscape feature that defined Goan identities. It was the rivers that

marked boundaries, whether prior to the arrival of the Portuguese or even

subsequent to their arrival. Indeed, in the first phase of Portuguese expansion

from the city of Goa, it was the rivers that provided boundaries for the realms

of the Portuguese Crown. As a fragment in Thakkar’s assemblage indicates, the

Portuguese armadas did not merely sail across the seas; they also sailed up the

rivers to assert their sovereignty over the city of Goa and other ports. Despite

engaging in trade across the seas, these ports were located upstream from the

sea. Until the advent of macadamised roads and petroleum-fuelled automotive

transport, it was the rivers that allowed for rapid transportation across the

various territories that today constitute Goa. It is little wonder, then, that

besides Viraj, the centrality of the river to Goan narratives is echoed by the

Goan poet Manohar Shetty’s collection of Goan short stories, titled Ferry Crossings (2000), while Reflected in Water (2006) is the name of

Jerry Pinto’s collection of writings on Goa. In fact, what is perhaps one of

the most famous conversations from the Goan cultural repertoire, between a

dancing girl and a boat man in the folk song Choltam Choltam, popularly known as hanv saiba poltodi voita, takes place on the bank of a river.  |

| "Cultural Conversation- 2", Viraj Naik |

There is no vibrant society that is not engaged in conversation, and it would therefore be presumptuous to accord to Goa any uniqueness in the conduct of conversation. And yet, ever since its birth as a city-state in the 1500s, and even prior to this period, Goa’s history has been marked by the presence of diverse actors and returning Goans, who have contributed to the sometimes bewildering diversity of this territory. Goa means many things to many people, and Goa is often reincarnated overseas by those who, after having departed from its shores, reimagine what Goa used to be. It is for this reason, then, that one can assert that indeed Goa não é um país pequeno.

(This blog was first published as part of the curatorial statement of the group exhibition of Goan artists, Goa não é um país pequeno, at Kalakriti art gallery, Hyderabad from 9 Feb to 28 Feb 2015.)

(My thanks to Viraj Naik for the opportunity to craft this essay, Christine Russon for her editorial help, and my colleagues at the Al-Zulaij Collective conversations with who aided the articulation of many ideas in the essay.)

(My thanks to Viraj Naik for the opportunity to craft this essay, Christine Russon for her editorial help, and my colleagues at the Al-Zulaij Collective conversations with who aided the articulation of many ideas in the essay.)

No comments:

Post a Comment