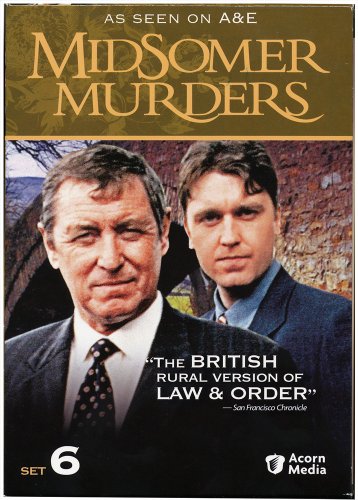

Over the past

couple of weeks I have been viewing back episodes of the British murder mystery

TV series Midsomer Murders. Set in

the fictional English county of Midsomer, the series revolves around the

efforts of Chief Inspector Detective Barnaby, who is attached to the CID of a

town called Causton, to resolve the murders that afflict the county.

Over the past

couple of weeks I have been viewing back episodes of the British murder mystery

TV series Midsomer Murders. Set in

the fictional English county of Midsomer, the series revolves around the

efforts of Chief Inspector Detective Barnaby, who is attached to the CID of a

town called Causton, to resolve the murders that afflict the county. A possible

reason for the attraction is that the series is a loving dedication to the English

countryside, and to the imagined English way of life. Midsomer Murders elevates what it sees as English reality with

great aplomb. There are long loving shots of breath-taking English countryside.

Added to this are the details that are worked into the stories: a focus on

contemporary English villages, the age-old social institutions, the rituals of

these institutions, the relationship between the gentry and the village-folk.

So lovingly ethnographic is the gaze of this series, that despite the glut of

murder and nastiness that fills these episodes one can’t help but feel how

wonderful it must be to live in rural England.

A possible

reason for the attraction is that the series is a loving dedication to the English

countryside, and to the imagined English way of life. Midsomer Murders elevates what it sees as English reality with

great aplomb. There are long loving shots of breath-taking English countryside.

Added to this are the details that are worked into the stories: a focus on

contemporary English villages, the age-old social institutions, the rituals of

these institutions, the relationship between the gentry and the village-folk.

So lovingly ethnographic is the gaze of this series, that despite the glut of

murder and nastiness that fills these episodes one can’t help but feel how

wonderful it must be to live in rural England. After a

substantial period of time, when I was more than a dozen or so episodes into

the drama, a rather discomfiting thought hit me. The series contained an

overwhelming number of white persons! It seemed as if there were no persons of

colour in the episodes. That is when I started actually looking for people of

colour and sure enough, not a single person in evidence!

After a

substantial period of time, when I was more than a dozen or so episodes into

the drama, a rather discomfiting thought hit me. The series contained an

overwhelming number of white persons! It seemed as if there were no persons of

colour in the episodes. That is when I started actually looking for people of

colour and sure enough, not a single person in evidence!

Reflecting on

this situation I was reminded of an

article that discussed the problems of race in video games. Mounting

responses to the standard apologies that one gets, the author Bao Phi phrased

one that has remained with me ever since, and seemed particularly appropriate

in the case of Midsomer’s

disappearance of English people of colour. The apology normally reads “Games

like Final Fantasy and Dragon Age are based in European folklore and there were

no people of color in Medieval Europe.” Phi’s response is clever and hits the

nail bang on the head: “Actually there were people of color in Medieval

Europe. You know what? There were more actual people of color in

Medieval Europe than there were REAL FIREBREATHING DRAGONS OR PEOPLE WHO COULD

SUMMON MOTORCYCLES OUT OF THIN AIR WITH THEIR MAGIC POWERS.”

This response

makes it so obvious that the constructions of our fantasies are not as innocent

as we make them out to be, but invariably involve a choice. That there were

more murderers in fictional Midsomer than people of colour suggests that the

producers of the show wished to show was that there was no space for people of colour in real English life and the

England of the imagination.

Something else

that struck me about Midsomer Murders

was the dramatic way in which it contrasted with American versions of the

similar genre like Castle, or Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

In the episodes that I have seen, Chief Inspector Barnaby and his associate

have practically never been shown with a gun. American versions of this genre,

however, are replete with the presence, and use, of guns. It should be pointed

out that I am unfamiliar with the way in which the police and detectives in

England actually operate. It is possible that just as the non-depiction of

people of colour highlighted the way the producers of Midsomer wished to imagine England, perhaps the depiction of a folksy

and unarmed police detective is also far from English reality. However, what is

important is the manner in which the ideal comportment of the police are

depicted. As suggested earlier, just as with advertising, television series

such as Midsomer Murders are

important because they set up an ideal world that we then look for in real

life. To this extent, Midsomer Murders

suggests that the use of guns is an aberration, while the American series

normalise the use of guns suggesting that the ONLY way in which law and order

can be enforced is via the use of guns.

Something else

that struck me about Midsomer Murders

was the dramatic way in which it contrasted with American versions of the

similar genre like Castle, or Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

In the episodes that I have seen, Chief Inspector Barnaby and his associate

have practically never been shown with a gun. American versions of this genre,

however, are replete with the presence, and use, of guns. It should be pointed

out that I am unfamiliar with the way in which the police and detectives in

England actually operate. It is possible that just as the non-depiction of

people of colour highlighted the way the producers of Midsomer wished to imagine England, perhaps the depiction of a folksy

and unarmed police detective is also far from English reality. However, what is

important is the manner in which the ideal comportment of the police are

depicted. As suggested earlier, just as with advertising, television series

such as Midsomer Murders are

important because they set up an ideal world that we then look for in real

life. To this extent, Midsomer Murders

suggests that the use of guns is an aberration, while the American series

normalise the use of guns suggesting that the ONLY way in which law and order

can be enforced is via the use of guns. Because

television is so ubiquitous in our lives it forms the basis of our expectations

of reality. For the great Indian middle class that feeds off American

television, American drama series offer a vision of what life in the USA is

like. Seeing police with guns, all too often their demand is that police in

India also be armed with guns. What they do not see is the kind of racist and

gratuitous violence that is meted out by police in the US to persons of colour,

and the fact that this violent tendency is aggravated by the carrying of lethal

weapons. Of course, given the caste-based nature of the Indian middle class, it

is perhaps something that they would not care too much about. Nevertheless, it

bears remembering that once unleashed, the spiral of violence is difficult to

contain.

Because

television is so ubiquitous in our lives it forms the basis of our expectations

of reality. For the great Indian middle class that feeds off American

television, American drama series offer a vision of what life in the USA is

like. Seeing police with guns, all too often their demand is that police in

India also be armed with guns. What they do not see is the kind of racist and

gratuitous violence that is meted out by police in the US to persons of colour,

and the fact that this violent tendency is aggravated by the carrying of lethal

weapons. Of course, given the caste-based nature of the Indian middle class, it

is perhaps something that they would not care too much about. Nevertheless, it

bears remembering that once unleashed, the spiral of violence is difficult to

contain.

It is not

uncommon to hear howls of protest whenever social justice issues are raised

vis-à-vis films and episodes on television. “Oh, but this is just fantasy” it

is claimed. Another standard trope is, “but film is about stereotypes!” Indeed,

televisual representation may be about stereotypes, but these representations also impact on our expectations of reality. It is for this reason that it is

critical that the representations in film and television are not simply

shrugged off as fantasy, but challenged not only to embody reality, but also

embody a just reality that we would like to see translated to reality.

(A version of this post was first published in The Goan Everyday on 30 Aug 2015)

No comments:

Post a Comment