I was recently greeted

at the airport in Dabolim by a most unpleasant advertisement. “It’s time to

claim your piece of Goa” read a large poster for Goa Paradise, a project by the

real-estate company Tata Housing. I saw the ad and was immediately consumed with rage.

I was recently greeted

at the airport in Dabolim by a most unpleasant advertisement. “It’s time to

claim your piece of Goa” read a large poster for Goa Paradise, a project by the

real-estate company Tata Housing. I saw the ad and was immediately consumed with rage.

Querying my

outrage, some friends suggested that there was nothing to get so mad about. “Why are you offended?” asked one, “it’s an ad meant to

sell properties that exist. I would not read much more into it. Locals sold,

others developed, now agencies sell.” To make matters clear, the problem with

the advertisement does not rest with “outsiders” purchasing property in Goa.

The problem lies in the manner in which the property is being marketed and

sold. It is the rhetoric through which the property is sold that goes on to

subsequently problematize the purchasing of this property.

Postcolonial scholars have pointed out that the problems with

European expansion was located in the act of claiming that agents of European crowns effected when they reached

the shores of America, Africa, and Australia. The problem with these acts of

claiming, such as the claiming of Australia for the Queen of England was that these

lands were not terra nullius or no

man’s land, but territories populated by numerous groups with their own laws,

sensibilities. This claiming subsequent to conquest disregarded the claims of

these people, and completed and continued the act of conquest. The word “claim”

continues to have those connotations, and it is this effective call to an act

of conquest that ensured that I found the ad offensive. While conquest may have

been a part of the game in times past, it is definitely not so in today’s

post-colonial world. One is welcome to

purchase property in Goa, but when this act of purchasing is converted into an

act of claiming or conquest, and opens the path for the consequent disregard of

the existing social fabric, it is transformed from a possibly quotidian act to

one of colonial violence.

Postcolonial scholars have pointed out that the problems with

European expansion was located in the act of claiming that agents of European crowns effected when they reached

the shores of America, Africa, and Australia. The problem with these acts of

claiming, such as the claiming of Australia for the Queen of England was that these

lands were not terra nullius or no

man’s land, but territories populated by numerous groups with their own laws,

sensibilities. This claiming subsequent to conquest disregarded the claims of

these people, and completed and continued the act of conquest. The word “claim”

continues to have those connotations, and it is this effective call to an act

of conquest that ensured that I found the ad offensive. While conquest may have

been a part of the game in times past, it is definitely not so in today’s

post-colonial world. One is welcome to

purchase property in Goa, but when this act of purchasing is converted into an

act of claiming or conquest, and opens the path for the consequent disregard of

the existing social fabric, it is transformed from a possibly quotidian act to

one of colonial violence. The violence of the advertisement was enhanced by presenting the

apartments being sold as “a piece of Goa”. The phrase “a piece of this” is not

without connotations. Advertisements work because they often tap into a deeper

conscious or unconscious collective understanding. Indeed, another real-estate venture, Aldeia de Goa, seem to have attempted a similar reference to "a piece of this" with an ad line that ran along the lines "If you want a piece of Goa you should become a piece of Goa". The sexual desire for a

person, when expressed as “I’d like a piece of him/her/that” is considered

offensive and sexist. It is considered offensive because the phrasing

transforms the individual, a subject deserving of dignity, into an object that

has no feelings, and can be possessed, used, and disposed of. This

understanding is also captured in the slang “You want a piece of me?” Often

used to challenge an adversary, in this case, the challenger is affirming that

s/he is not an object, and will not stand for such treatment. The Aldeia de Goa ad was saved from substantial critique only because it suggested that one had to become a part of Goa, a piece of it, and not merely purchase one's piece of the territory.

The violence of the advertisement was enhanced by presenting the

apartments being sold as “a piece of Goa”. The phrase “a piece of this” is not

without connotations. Advertisements work because they often tap into a deeper

conscious or unconscious collective understanding. Indeed, another real-estate venture, Aldeia de Goa, seem to have attempted a similar reference to "a piece of this" with an ad line that ran along the lines "If you want a piece of Goa you should become a piece of Goa". The sexual desire for a

person, when expressed as “I’d like a piece of him/her/that” is considered

offensive and sexist. It is considered offensive because the phrasing

transforms the individual, a subject deserving of dignity, into an object that

has no feelings, and can be possessed, used, and disposed of. This

understanding is also captured in the slang “You want a piece of me?” Often

used to challenge an adversary, in this case, the challenger is affirming that

s/he is not an object, and will not stand for such treatment. The Aldeia de Goa ad was saved from substantial critique only because it suggested that one had to become a part of Goa, a piece of it, and not merely purchase one's piece of the territory.

As scholars have pointed out, the act of claiming, or the act of any

conquering power, is an act of patriarchal power. It sees territory as female,

appropriate for exploring, dominating and consuming. It is, therefore, not

surprising that Tata Housing clubbed the “claim” with “piece of”.

But Goa is emphatically not

merely a piece of territory that can be claimed, or broken up into individual

pieces. While an exotic destination for some, and alluring real estate location

for others, it is also the home to hundreds of thousands of people. Having

lived here for generations, they have evolved a certain lifestyle on the land.

Purchasing property in Goa must mean creating an option to participate in this

lifestyle, and in a way that is respectful of those for whom who live here. To

set up the purchasing of property as an act of conquest that disregards the

context in which this property is located, is an act of profound violence and

disrespect to the persons who have lived here for generations, and for whom

this is the only home they have.

Another response to my outrage over the ad argued; “When Goans

‘claim a piece’ in London or Swindon, Melbourne or Lisbon (including the

official residence of PM) why should others not clam a ‘piece of Goa’?” This is

a common counter to the concerns raised by Goans about the way their territory

is rapidly changing. What needs to be underlined is that the relationship

between purchasers of property in Goa, and average Goans is not one of

equality. A good number of Goans cannot

in fact purchase property in other locations where they migrate to work. Many

Goans who travel to Swindon are most certainly not purchasing property there,

but living in miserable conditions that approximate Dickensian descriptions of the

labouring masses’ lodgings in Victorian England. Further, as migrants who move

to other locations, they are not powerful actors engaged in conquest of these

territories, but persons merely seeking a life that was denied to them in their

natal territories. To equate the prospective purchaser of Goa Paradise with the

migrant is an act of colonial violence perpetuated by local elites who have no

reason to move from Goa, and see a possibility of integrating into the emerging

socio-political order where Goa is seen as a location that can be conquered and

dominated.

Another response to my outrage over the ad argued; “When Goans

‘claim a piece’ in London or Swindon, Melbourne or Lisbon (including the

official residence of PM) why should others not clam a ‘piece of Goa’?” This is

a common counter to the concerns raised by Goans about the way their territory

is rapidly changing. What needs to be underlined is that the relationship

between purchasers of property in Goa, and average Goans is not one of

equality. A good number of Goans cannot

in fact purchase property in other locations where they migrate to work. Many

Goans who travel to Swindon are most certainly not purchasing property there,

but living in miserable conditions that approximate Dickensian descriptions of the

labouring masses’ lodgings in Victorian England. Further, as migrants who move

to other locations, they are not powerful actors engaged in conquest of these

territories, but persons merely seeking a life that was denied to them in their

natal territories. To equate the prospective purchaser of Goa Paradise with the

migrant is an act of colonial violence perpetuated by local elites who have no

reason to move from Goa, and see a possibility of integrating into the emerging

socio-political order where Goa is seen as a location that can be conquered and

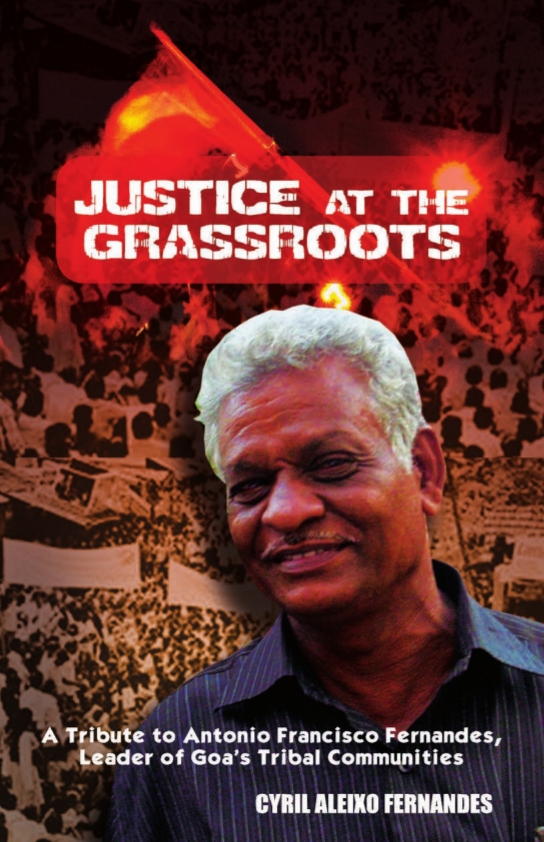

dominated. Further, thanks to the inflated prices caused by the big money

chasing ‘their own piece’ of the place most ordinary Goans are in fact not able

to purchase property in Goa too, nowadays. This is precisely the reason why the

tribal activist Antonio Francisco Fernandes demanded that the government of Goa

guarantee housing to all Goans from indigenous communities.

Further, thanks to the inflated prices caused by the big money

chasing ‘their own piece’ of the place most ordinary Goans are in fact not able

to purchase property in Goa too, nowadays. This is precisely the reason why the

tribal activist Antonio Francisco Fernandes demanded that the government of Goa

guarantee housing to all Goans from indigenous communities.

The advertisement of Tata Housing is sexist and profoundly offensive

and it must be prevailed upon to withdraw this advertisement at the earliest.

(A version of this post was first published in the O Heraldo on 22 Jan 2016)