Last Christmas season my family

and I fled tourist-invaded Goa for some peace and quiet. Little did we realize,

despite friendly advice, that our destination, Sri Lanka, was also one of those

holiday favourites that gets flooded at Christmas time. Along the five days

that we were on the island, in addition to experiencing the incredible beauty

of the country, we were also forced to spend much of our time in traffic jams,

whether in the capital city Colombo, in Kandy, home of the famous Temple of the

Tooth, or on the roads between these two cities.

I had been to the island-state

some years prior to this family holiday, and I am sure that the country I

witnessed was entirely different in terms of the amount of traffic that one

experienced. If anything, my journeys then were experiences of smooth flows

from one destination to another. It appears that the end of the decades-long

civil war may have released extra income into the economy creating the kind of

spurt in traffic that one witnessed on my last trip.

Yet, despite the fact that we

spent a good amount of time in traffic jams our experience of traffic in Sri

Lanka was not the same as that in India, and/or Goa. A traffic jam in India is

an occasion for tons of honking and attempts by individuals to cut through the

traffic jam by getting onto the opposite lane and charging to the head of the

line. Others follow the lead of the first offender which ensures that within a

matter of minutes the jam has been complicated beyond imagining and that

instead of two lanes, one has multiple lanes, tempers rise and what could have

been resolved within a shorter time takes forever to be repaired.

In the course of the short stay

in Sri Lanka my experiences of traffic jams were anything but similar. To begin

with traffic jams were the result not of indiscipline, but because of the usual

reason for the phenomena, too much traffic on small lanes. Rather than cut

across lanes and try to short circuit the system people waited patiently for

the traffic to move. It took us a couple of minutes to realize that our experience

of the first jam in Sri Lanka was different from what we encountered in India.

There was no honking! So strange was the situation that we could just not

contain ourselves, and kept repeating this fact, over and over again, to

ourselves, and then when we returned home to every one we met.

In the course of the short stay

in Sri Lanka my experiences of traffic jams were anything but similar. To begin

with traffic jams were the result not of indiscipline, but because of the usual

reason for the phenomena, too much traffic on small lanes. Rather than cut

across lanes and try to short circuit the system people waited patiently for

the traffic to move. It took us a couple of minutes to realize that our experience

of the first jam in Sri Lanka was different from what we encountered in India.

There was no honking! So strange was the situation that we could just not

contain ourselves, and kept repeating this fact, over and over again, to

ourselves, and then when we returned home to every one we met. How can this difference between

the road experience in India and Sri Lanka be explained? While in Sri Lanka I

did notice that there were clear signs, at least in Colombo, indicating that

lane discipline had to be maintained at all time, and the presence of traffic

police at regular intervals. Speaking with the driver of the cab we employed we

got the sense that the police are invariably on hand to take any offender to

task. Responding to our queries he also suggested that it was unlikely that the

police would accept bribes from offenders.

How can this difference between

the road experience in India and Sri Lanka be explained? While in Sri Lanka I

did notice that there were clear signs, at least in Colombo, indicating that

lane discipline had to be maintained at all time, and the presence of traffic

police at regular intervals. Speaking with the driver of the cab we employed we

got the sense that the police are invariably on hand to take any offender to

task. Responding to our queries he also suggested that it was unlikely that the

police would accept bribes from offenders. In the course of our journey, as

we grew close to our driver, he shared much with us about his country. What I

would like to focus on, as I try and resolve this question of the traffic discipline

in Sri Lanka, is his narratives about the State. He spoke about the health care

system that offered free, reliable and dependable service to all Sri Lankans.

Trying to build a pattern from all that I had heard from him, I realized that

in Sri Lanka the people were assured of an ever present state that was

reliable, and dependable. I doubt that the same could be said about India.

In the course of our journey, as

we grew close to our driver, he shared much with us about his country. What I

would like to focus on, as I try and resolve this question of the traffic discipline

in Sri Lanka, is his narratives about the State. He spoke about the health care

system that offered free, reliable and dependable service to all Sri Lankans.

Trying to build a pattern from all that I had heard from him, I realized that

in Sri Lanka the people were assured of an ever present state that was

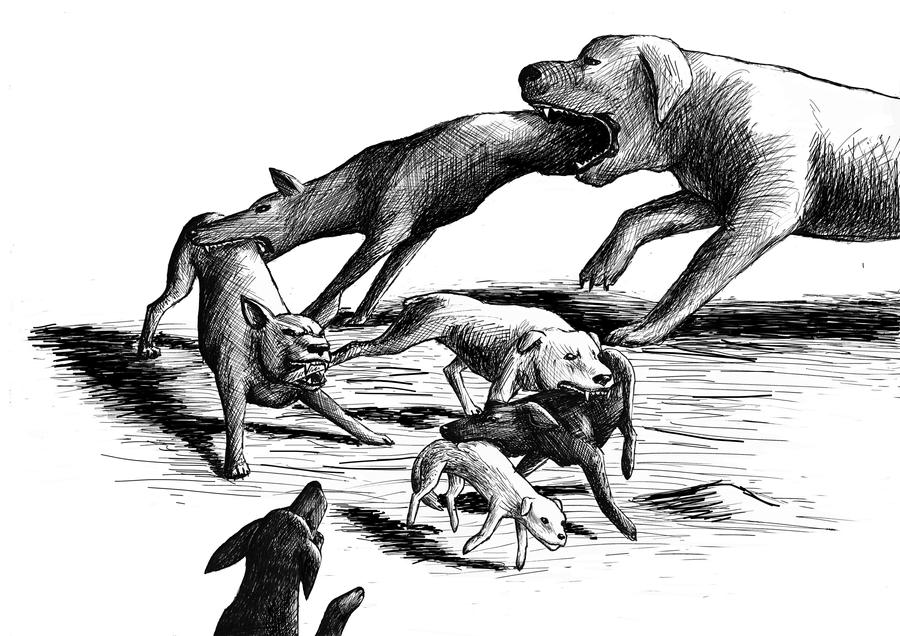

reliable, and dependable. I doubt that the same could be said about India.  In India, one knows that one

cannot rely on the state to maintain the law. The infrastructure of the state

is invariably seen as tools to enrich those who gain access to public office.

The enforcement of the law is not uniform. Any one in Goa will acknowledge that

if one has connections to the officer’s superiors one can get away not only

without a fine, but after having insulted the traffic officer. In other words,

in India one knows that the state will not look after you, nor will it work to

create a level playing ground. You have to look out for yourself in a dog eat

dog world. In other words, it is not rules that help you get ahead in India,

but the violation of rules, and muscling in on a scene gives you more than

waiting patiently in line. The absence of a traffic etiquette in India is

therefore the result of a failed state.

In India, one knows that one

cannot rely on the state to maintain the law. The infrastructure of the state

is invariably seen as tools to enrich those who gain access to public office.

The enforcement of the law is not uniform. Any one in Goa will acknowledge that

if one has connections to the officer’s superiors one can get away not only

without a fine, but after having insulted the traffic officer. In other words,

in India one knows that the state will not look after you, nor will it work to

create a level playing ground. You have to look out for yourself in a dog eat

dog world. In other words, it is not rules that help you get ahead in India,

but the violation of rules, and muscling in on a scene gives you more than

waiting patiently in line. The absence of a traffic etiquette in India is

therefore the result of a failed state. In sum, it seems that if there is

a difference between traffic behavior in Sri Lanka and India, the reason can be

pinned down to the fact that at least at the level of the average citizen, the

Sri Lankan state is seen to be a neutral arbiter of rules that are taken

seriously, while in India, one knows that the state has abandoned its role and

made way for the so-called laws of the jungle to take root.

In sum, it seems that if there is

a difference between traffic behavior in Sri Lanka and India, the reason can be

pinned down to the fact that at least at the level of the average citizen, the

Sri Lankan state is seen to be a neutral arbiter of rules that are taken

seriously, while in India, one knows that the state has abandoned its role and

made way for the so-called laws of the jungle to take root.

(A version of this post was first published in The Goan, on 10 April 2016)