If you were travel up to north

India, say to cities like Lucknow, or Agra, and had conversations with the

‘small’ folk, or just people who had lived for generations, and whose lives did

not involve some kind of grand rupture, you would hear references to a

Rani Todiya, or

Mallka Todiya.

Rani Todiya

is used by such folk, as a marker of time; invariably of the good old days,

when things were cheap, when life was simpler, when there was a rule of law.

What is interesting however, is that these folk are not referring to some

Satyayug deity, but of the Queen-Empress

Victoria; the Victoria being compressed to

Todiya.

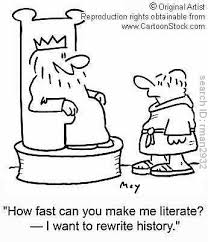

What is interesting about this term for Victoria is that not only is her reign

the marker for the good times, but it is also evidence of the manner in which

she had been internalized. Not only was her name transformed into a vernacular

form, but her position in society, as ‘their’ or ‘our’ Queen, was also to a

large extent internalized. The Empress Victoria reigned over an entire

psycho-social edifice, an edifice that transcended the seven seas,

incorporating native-rulers, castes, panchayats, producing in this manner, the

British Raj. The Raj to that extent was very ‘Indian’, as much as

Rani Todiya was our queen. This may come

as a surprise for those who have been raised on the nationalist intellectual

frameworks in use in schools. Frameworks that suggest to us, that there was

always an ‘us’ and a ‘them’ between the British and the Indians. What these

frameworks forget to mention however, is that when

Todiya was made our Queen, it was not just she who had a right over

us, but as is necessary in any form of kingship, we too had a claim on our

kings (and queens).

In a similar manner then, what we

in Goa, given the spectacular disinclination to teach our history in schools,

have largely forgotten, is that in addition to claiming the Portuguese kings

and queens as our own, we can also rightfully lay claim to three Spanish kings.

From 1580 until 1640,

the Portuguese crown was united with the Spanish crown,

allowing for two separate kingdoms, but just one King; a situation that ran its

course under the three Hapsburg Phillips of Spain.

With such a history in mind, the

Goan traveling in Europe has not merely a Portuguese link with that continent,

but larger European link. When traveling in the Netherlands, one thinks not

merely of the Dutch opponents of the early Estado da India Portuguesa, but also

of the fact that the Netherlands were once upon-a-time part of the Hapsburg

domains. Domains lost in the course of the wars that broke out in the continent

in the course of the Reformation. Similarly, when one travels to the one-time

imperial capital of Toledo in Spain, one does not start when one sees those

large double-headed eagles clutching the arms of the Hapsburg kings in their

talons. On the contrary, the emotion that one is faced with is that of pleasant

surprise when encountering the familiar. For did we not already see this motif

in Old Goa, proudly recording the sovereignty of Phillip, king of all of

Iberia?

The journey to Portugal was not,

as this column so often points out, to reconstruct some empty colonial saudadismo with regard to Portugal. On

the contrary, the trip to Portugal was to figure out if there were other ways

in which our relation to this country could be rearticulated in a contemporary

context. This contemporary context would not include only the examination of

the manner in which we can relate as South Asians, members of the Indian ocean

world, and as Indians, to Portugal. This

movement would also mean embracing its complex (sometimes obscured) histories

and giving them new relevance and meaning. In the course of this embrace, we are not bound to the nationalist interpretations of this history that the Portuguese may feel obliged to produce. On the contrary, we can legitimately rewrite this history from our own point of view. Embracing this history, making it

genuinely our own, allows us, in the manner that Mallka Todiya was claimed by her Indian subjects, allows us to make

similar claims on the heritage of the Philippine emperors. This claim of

inheritance should not ofcourse only be narrowly read, or shortsightedly

utilized, but more properly embraced, so that we effectively become citizens of

the world, a marked characteristic of the Goan (often an emigrant into this

large world).

Some may find this suggestion of embracing an Imperial heritage, especially by former subjects of the Empire, problematic. There is no denying that such an embrace is problematic. However, we should recognize that this embrace, while possibly problematic, also comes with its fair share of empowerment. It allows the contemporary resident of the global South, to go to foreign lands, in the knowledge that these lands that must today be crafted into home, were in earlier times, also home. This embrace also allows us to transcend the binaries of 'us' and 'them' and recognize commonalities that unite us outside of the frames that we normally use to see ourselves; constructing in this manner a common humanity.

Speaking of embracing this larger

heritage, and seeing ourselves outside of the frames we normally use, most

people would be surprised to realize that urinating on the street is not

particularly a crass Indian habit. All too often, one is apt to find

contemporary descendants of Philippine subjects, be they male or female, easing

themselves on the streets, especially late at night over the course of the

weekend. Come to think of it, this is not, and was not a practice unfamiliar in

the former realm of good Rani Todiya either! Some uncommon embraces it appears, can

engender uncommon perspectives.

While there

seems no particular concern among the nabobs of the subcontinent to transform

themselves into well-rounded gentleman, should a Grand Tour be contemplated for

denizens of the sub-continent, then Sri Lanka must definitely be listed as a

must-do on this subcontinental tour. Travelling to Sri Lanka, engaging with its

past, especially, but not only, its medieval and ancient past gives one a

completely different perspective, not only on South Asia, but Asia as well.

Situated at one end of this continental agglomeration, Sri Lanka affords one a

vista of two rims of the Indian Ocean world, and perhaps their rather different

dominant logics. To the left of the emerald isle lies the largely Islamicate

world of the Arabian sea, and to the left, the Buddhic world of the Bay of

Bengal.

While there

seems no particular concern among the nabobs of the subcontinent to transform

themselves into well-rounded gentleman, should a Grand Tour be contemplated for

denizens of the sub-continent, then Sri Lanka must definitely be listed as a

must-do on this subcontinental tour. Travelling to Sri Lanka, engaging with its

past, especially, but not only, its medieval and ancient past gives one a

completely different perspective, not only on South Asia, but Asia as well.

Situated at one end of this continental agglomeration, Sri Lanka affords one a

vista of two rims of the Indian Ocean world, and perhaps their rather different

dominant logics. To the left of the emerald isle lies the largely Islamicate

world of the Arabian sea, and to the left, the Buddhic world of the Bay of

Bengal.