Ever since the

Indian army marched in and annexed the Portuguese State of India to the Union,

Goan society has been involved in an incredibly intense churning. This churning

has occurred as Goans sought, and continue to seek, their location within the

larger Indian polity; as they sought to make sense of the rapid changes that

overturned the social structures of a highly stratified society held in place

through late Portuguese imperialism; as new elites emerged and waves of, until-then,

foreigners landed up to radically transform the Goan landscape. A churning that

has been on for some decades now, it would not be wrong to say that this

process reached a particularly intense moment in the past couple of years. It

is within this context that

Let me tell

you about Quinta should be read, evaluated and appreciated. A good number

of Goan, and non-Goan artists, musicians and writers have attempted to grapple

with the upheavals that have beset Goan society, and it must be said that

Let me tell you is clearly one of the

finer products of that churning.

Set in the

village of Carmona,

Let me tell you about

Quinta is narrative that spans three generations (including an illegitimate

one) of a Catholic

bhatcar (i.e. landed Goan)

family and its multiple Others. Weaving between time-periods, pre-colonial, colonial

and the post-colonial, the narrative is punctuated by the voice of the initial

narrator of the epic, and the figure closest in time to us; the readers. Indeed,

the delicate texture of time that this narrative produces is one of the finer

features of this book, fine-grained in its attention to detail, yet never

leaving one exhausted from the burdens of history. And yet, the central

protagonist of the narrative is clearly

Quinta

do Santo Antonio the highly contested property that, like so many Goan

homes and properties of the late-colonial epoch, framed the emergence, lifestyles

and the eventual dissolution of one class and the burgeoning of another. This

grand Goan home, like others in the territory, measured carefully the lives its

owners would lead, and mapped the relationships they would enjoy or suffer with

their relatives and minions; living on, even as the eaves of these homes

eventually come crashing down. It should be said, that one could use this one

book as a fairly effective way into getting into a broad and yet sensitive

understanding of Goan society and its history.

Let me tell you

Let me tell you however, does not limit

itself to merely weaving its tale via reference to the quotidian. On the

contrary, the magical or the enchanted trespass quite frequently into the tale,

be it in the form of birthing fluids that deluge automobiles, women who speak

quite casually to spirits that tattle tales of buried wealth, and curses that

eventually ruin families. If it were just this however,

Let me tell you would fall well into the realm of fantasy, or

magical realism. However, because the fantastic that the narrative presents are

from well within the vernacular traditions of Goa, this book is poised quite

comfortably within the realm of contemporary mythology. The most exciting

feature of this book therefore is not the deft weaving of Goan history, or its

sociological insight, but the manner in which it has done both of these while

integrating the same into the spiritual traditions of the land. Most efforts on

this front, especially by Goan Catholic authors tend to tumble headlong into an

embrace of brahmanical myth, as they thrash about seeking to recreate the

history of a Hindu past that they believe they have lost. Not so

Let me tell you, that catholically

embraces the fluid movements of Goan history while simultaneously rooting itself

in a living and breathing mythological traditions of village Goa, or perhaps

more appropriately village Salcette (the

taluka

within which the novel is so firmly set.)

Because

Let me tell you emerges from out of this

great Goan soul-searching, because it is located within the mythos of the Goan

space,

and because it is cognizant of

the nuances that time has wrought on this space, it is an intensely political

text. Like the time-frame of the narrative, this commentary is pronounced upon

various locations of Goan time, not restricting itself merely to the

contemporary moment. However, because it is

Quinta

that is the central figure of the book, the most fundamental comment is the

lament for the loss of the Goan homes and the families that built them. Take for

example this hugely evocative “‘What a life’ wrote Preciosa to Sun, ‘this was a

land of open door, now we have to lock ourselves in to avoid people.’”

And yet, while the narrative mourns the

passing of an age, because it reflects on the morality of the actions that

built and sustained those home, and eventually came to pass, it is a cathartic lament,

creating through this narrative the legitimate space for those former

subalterns, the minions of homes like

Quinta

do Santo Antonio who have now come to succeeded to the Goan earth that they

were so long disinherited from.

For the

dexterity with which Savia Viegas weaves these many projects together, for its

breathless and graphic storytelling, the book is an intellectual delight even

if one is not interested in Goa, its politics or its history. Indeed, because

of the manner in which it involves itself with the genealogies of a creole

society, a number of readers have commented on, and drawn parallels with the

works of Marquez and Allende. However, those unfamiliar with the nuances of

Goan cuisine, language, hierarchies and idiosyncrasies may at times find it

difficult to navigate and make sense of the narrative. Viegas, or the

publishers Penguin, would have been well advised to include a glossary along

with the narrative. However, one could also perhaps simultaneously discern from

this lack of a glossary, the decision to pluck Goa away from its location as an

aberration, where it is merely ‘a small part of India’ and return to it its

universal significance. While on the subject of language, it should also be

said that the few forays that the narrative makes into other languages, be it

Hindi, Konkani or Portuguese detract from the breathless beauty of the narrative.

One can understand the temptation to invoke the vernaculars to give a flavor of

the land, but given Viegas’ skills that have thus far been acclaimed, these

little flourishes serve only a cloying flavor that could have well be dropped.

Introducing the vernacular tongue into a text written in a different idiom is

seldom easy, and this attempt is not Viegas’ brightest moment. There is another

grumble associated with language and this one involves the dropping of the

accents that communicate the sounds of the Portuguese language used in the

book. This, along with spelling errors, is often a ‘mistake’ committed by

Anglophone publishers of texts that invoke languages other than English. For a

text that seeks to weave the Portuguese language convincingly into its

narrative however, this is an appalling oversight.

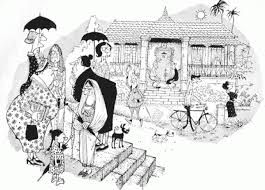

The last of the

grumbles associated with the production of this book involves the images

located in the text. Five in number, Viegas commences each part of this

four-fold narrative with a pictograph assumedly crafted by her hand. These

images share an interesting relationship with the text. Not quite a

show-and-tell, it is as if these images are the remnants of the dreams from

which the narrative was born. Given that these images would been executed in colour,

and given their association with the text, it is a shame that they appear in

the book not in the lavish colour or Viegas’ no doubt technicolour dreams, but

in muted and disappointing shades of greys.

Savia Viegas’s

book is a delight at so many levels; so do, do let her tell you about Quinta.

Let Me Tell You About Quinta

By Savia Viegas

Penguin Books India, New Delhi, 2011, 254 pp., Rs 299

ISBN 0143415220

No comments:

Post a Comment