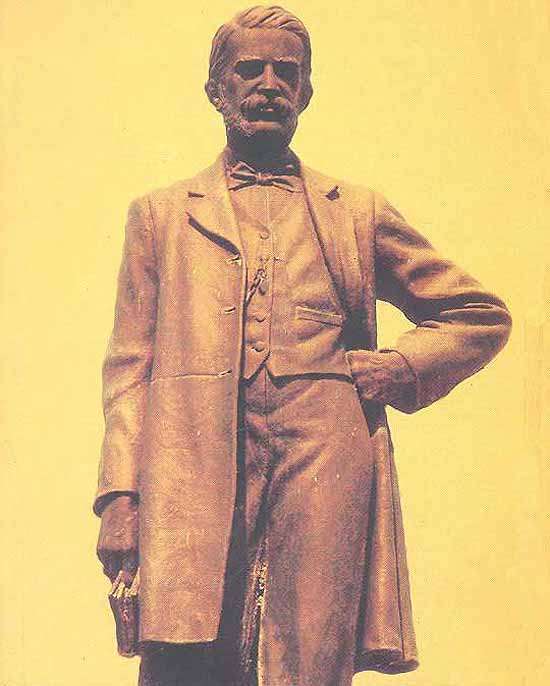

In his essay “The Lusitanian in Hind”

for the magazine Outlook India (2

September, 2013), novelist Aravind Adiga strives to situate the 19th

century Goan writer and politician Francisco Luis Gomes (1829-1869) as an

Indian patriot while decrying how “most Indians [have] not heard about Gomes,”

which to Adiga “speaks more about the narrowness of our present conception of

Indianness [...].” Yet, through his essay, Adiga further perpetuates the very

narrowness he warns against. In trying to resuscitate national and

nationalistic interest in Gomes, Adiga explores the possibility of the Goan

polymath’s canonicity solely within a prescriptive Indianness hemmed in by

Brahmanical, masculinist, Anglo-centric, and ethnocentric preconceptions of

what it means to be Indian. In Adiga’s estimation, Gomes can only be made

legible to the larger Indian imagination if, as a Goan of the Portuguese

colonial era, he can be seen as adequately Indian based on elitist

particularities of caste and other constricted views of proper national and

historical belonging.

In his essay “The Lusitanian in Hind”

for the magazine Outlook India (2

September, 2013), novelist Aravind Adiga strives to situate the 19th

century Goan writer and politician Francisco Luis Gomes (1829-1869) as an

Indian patriot while decrying how “most Indians [have] not heard about Gomes,”

which to Adiga “speaks more about the narrowness of our present conception of

Indianness [...].” Yet, through his essay, Adiga further perpetuates the very

narrowness he warns against. In trying to resuscitate national and

nationalistic interest in Gomes, Adiga explores the possibility of the Goan

polymath’s canonicity solely within a prescriptive Indianness hemmed in by

Brahmanical, masculinist, Anglo-centric, and ethnocentric preconceptions of

what it means to be Indian. In Adiga’s estimation, Gomes can only be made

legible to the larger Indian imagination if, as a Goan of the Portuguese

colonial era, he can be seen as adequately Indian based on elitist

particularities of caste and other constricted views of proper national and

historical belonging.

While Adiga notes how Goa generally

registers in popular Indian thought “as a landscape of fun,” he also pre-empts

any discussion of the history of the region apart from modern India, and the

impact of such historical regionality upon Gomes’ own oeuvre. Instead, when

citing Gomes as having written of himself that he “was born in India, cradle of

poetry, philosophy and history, today its tomb,” Adiga rushes to correlate such

sentiment with Gomes having penned those words in 1861 which, in turn, would

make one suppose “[naturally] enough that [the] author was a Bengali Hindu,

writing either in Calcutta or London.” However, as Adiga interjects, “[Gomes] was

a young Goan Catholic in Lisbon [...].” Clearly, Adiga endeavours to draw

attention to the biases that exist in how perceptions of patriotism connote an

Indianness circumscribed by location, coloniality, and religion. Nonetheless,

rather than striking a contrast for deeper critical reflection on difference,

Adiga’s purpose is to collapse all distinction into nationalist similitude as

if it were “natural.”And what is believed to be natural here is that Goa can be

a known quantity precisely because there allegedly is no difference between it

and British-colonised Hindu Bengal, which at once reveals what the historic,

religious, ethnocentric, and colonial default of the nation is as Adiga

predicates it in this ostensibly neutral reasoning.

There is no denying that there were

overlaps, and even collusions, between British and Portuguese colonialisms, but

there were also marked differences. Although relegating it to a parenthetical aside,

even Adiga must admit that “[u]nlike Britain, Portugal gave its colonies the right

of representation.” This was an opportunity that was not available to the sub-continental

subjects of the British Crown, not even to Dadabhai Naoroji who even while he may

have been the first Asian in the British Parliament, was able to raise issues

about British India only while representing a constituency in London. In

contradistinction, it was from his position as a representative of Goa in the

Portuguese parliament that Gomes sought to speak about the effects of

colonialism on his Goan homeland and about India. Nowhere is this more apparent

than in his book Os Brahmanes, or The Brahmins, written in Portuguese and

published in Lisbon in 1866, making it one of Goa’s, if not India’s, first

novels. What might Adiga do with other divergences in histories between the

former British and Portuguese Empires in India? Not only was the latter a

longer colonisation, witnessing radically different forms of inclusion and

exclusion of the colonised, it also resulted in the decolonisation of Goa in

1961, much after British-occupied India. His essay can only sidestep the

fraught history of India’s “democracy” in which Goans were not allowed self-determination

despite much evidence of efforts in that vein. This is itself a political

trajectory within which one could arguably place Gomes’ own polemical writing.

There is no denying that there were

overlaps, and even collusions, between British and Portuguese colonialisms, but

there were also marked differences. Although relegating it to a parenthetical aside,

even Adiga must admit that “[u]nlike Britain, Portugal gave its colonies the right

of representation.” This was an opportunity that was not available to the sub-continental

subjects of the British Crown, not even to Dadabhai Naoroji who even while he may

have been the first Asian in the British Parliament, was able to raise issues

about British India only while representing a constituency in London. In

contradistinction, it was from his position as a representative of Goa in the

Portuguese parliament that Gomes sought to speak about the effects of

colonialism on his Goan homeland and about India. Nowhere is this more apparent

than in his book Os Brahmanes, or The Brahmins, written in Portuguese and

published in Lisbon in 1866, making it one of Goa’s, if not India’s, first

novels. What might Adiga do with other divergences in histories between the

former British and Portuguese Empires in India? Not only was the latter a

longer colonisation, witnessing radically different forms of inclusion and

exclusion of the colonised, it also resulted in the decolonisation of Goa in

1961, much after British-occupied India. His essay can only sidestep the

fraught history of India’s “democracy” in which Goans were not allowed self-determination

despite much evidence of efforts in that vein. This is itself a political

trajectory within which one could arguably place Gomes’ own polemical writing.

In his haste to employ a

one-nationalism-fits-all approach, Adiga’s lauding of Gomes as a forgotten

patriot occurs, furthermore, along the lines of an unquestioning maintenance of

religious and other supremacies as the default of proper Indianness. One way the

article effects this is by privileging narratives of upper caste loss. For

instance, Adiga posits the notion that it was “[t]he brutal start of Portuguese

rule in Goa in 1510” which caused Saraswat Brahmins “to flee their homeland in

order to protect their faith [...].” This according to him was a “boon for

modern India,” as the Saraswats “fertilis[ed] commerce and culture everywhere

they went.”

Yes, under the leadership of Afonso de

Albuquerque, there was much bloodshed of the residents of the city of Goa by

the Portuguese in the early sixteenth century; strikingly, many of these

victims were the soldiers of Adil Shah who, like the Bijapuri ruler of the

city, happened to be Muslim. Albuquerque is in fact said to have declared that Muslims

were enemies and the “gentiles” friends, which is not surprising given that he

was aided in his conquest by the army of Saraswat chieftain Mhal Pai, after

being invited by Timayya, agent of Vijayanagara, to capture the city in the

first place. These allies buttressed the more preponderant contestation between

the Portuguese and the ‘Moors’ for trading rights and privileges in the Indian

Ocean. Some Brahmins did flee, as did members of other caste and religious

groups who do not factor into Adiga’s retelling; consequently, their

contribution to India is forgotten rather than celebrated as a “boon.” It must

be pointed out that some Brahmins and others even opted to convert to Christianity. As recent research has shown, not all conversions were forced,

but were calculated decisions taken by members of various groups. Moreover, in

the last few years, scholars like Pankaj Mishra and Goa’s Victor Ferrão have

questioned the idea that Hindus, as they are known today as a faith group,

pre-existed the orientalist efforts of colonisers to classify, and lump

together, discrete religious sects into one category. In addition, Adiga does

not reckon with how members of the upper caste echelon who lived on in Goa

sought to preserve their authority within the machinations of colonialism. As

in other parts of India, Goa too bore witness to the collaboration between

colonisers and higher caste groups in order to strengthen domination based on

existing hierarchies.

Yes, under the leadership of Afonso de

Albuquerque, there was much bloodshed of the residents of the city of Goa by

the Portuguese in the early sixteenth century; strikingly, many of these

victims were the soldiers of Adil Shah who, like the Bijapuri ruler of the

city, happened to be Muslim. Albuquerque is in fact said to have declared that Muslims

were enemies and the “gentiles” friends, which is not surprising given that he

was aided in his conquest by the army of Saraswat chieftain Mhal Pai, after

being invited by Timayya, agent of Vijayanagara, to capture the city in the

first place. These allies buttressed the more preponderant contestation between

the Portuguese and the ‘Moors’ for trading rights and privileges in the Indian

Ocean. Some Brahmins did flee, as did members of other caste and religious

groups who do not factor into Adiga’s retelling; consequently, their

contribution to India is forgotten rather than celebrated as a “boon.” It must

be pointed out that some Brahmins and others even opted to convert to Christianity. As recent research has shown, not all conversions were forced,

but were calculated decisions taken by members of various groups. Moreover, in

the last few years, scholars like Pankaj Mishra and Goa’s Victor Ferrão have

questioned the idea that Hindus, as they are known today as a faith group,

pre-existed the orientalist efforts of colonisers to classify, and lump

together, discrete religious sects into one category. In addition, Adiga does

not reckon with how members of the upper caste echelon who lived on in Goa

sought to preserve their authority within the machinations of colonialism. As

in other parts of India, Goa too bore witness to the collaboration between

colonisers and higher caste groups in order to strengthen domination based on

existing hierarchies.

These details fail to appear in

Adiga’s narration because he predominantly restricts his understanding of Goan

history to the mythologies of the Saraswat caste. In so doing, he also misrepresents

the fact that the Saraswat caste was already well established through the

length of the Konkan coast prior to the arrival of the Portuguese. It was this coastal

predominance that allowed the Saraswats to operate as interlocutors for the

Portuguese, as well as to ensure that those Brahmins who chose not to convert

were able to migrate to places where they were not entirely without some social

and cultural capital. The casting of Goa as a Saraswat homeland was a feature

of nineteenth century Goan politics, a politics supported in equal measure by

Catholic as well as Hindu Brahmin elites as they both sought to jockey for

greater power. For the latter group, in particular, their power struggle was to

secure a regional fiefdom in Goa against the supremacy of the Marathi-speaking

Brahmin groups in Bombay city.

As Adiga repeatedly points out,

despite the privileges accorded to some natives in the Portuguese colony, even

elite Goans found themselves “doomed to a second-class existence.” Of Gomes’

own trial by fire at the onset of his time in the Portuguese parliament, Adiga

states that the Goan politician “heard another member demand that the

government rescind the right given to colonial savages to sit in a civilised

parliament.” This caused Gomes to wax eloquently about the civility of Indic

cultures in educating his parliamentary counterparts, a group Adiga refers to

as “the carnivorous Europeans.” What is the purpose of such an authorial

statement other than to ascribe some notion of purity to one group over another

along the lines of casteist exclusion? While it serves to characterise

Europeans as uncouth because of their presumed dietary habits, it can only do

so by participating in the logics of defilement used against the many marginalised

peoples in India and, perhaps, meat-eating Goan Catholics, a group that Gomes

himself belonged to. Though that irony seems to escape Adiga, it nevertheless

continues to establish a sense of Indianness in the article that strongly veers

toward Brahmanical Hindu nationalism.

The bent of such nationalism is made

even more explicit when Adiga likens Gomes to Vivekananda. The essay purports

that the two had similar visions of emancipation: “Vivekananda saw education

and the renaissance of Hinduism as the answer. Gomes, who believed Hinduism was

spent, pointed to education and Christianity.” As one might expect of a novel titled Os Brahmanes, the book – like

Gomes’ own politics and thinking – is not without orientalist or elitist

notions. Albeit, in describing some of Gomes’ narrative as being “Orientalist

escapism,” Adiga spotlights the novelist’s indignation at the inherent

contradictions of European colonialism. The essay quotes Gomes’ novel as

declaring that if “the law of Christ governs European civilisation [...] [i]t

is a lie – Europe tramples upon Asia and America, and all trample upon poor

Africa – the Black races of Africa are the pariahs of the Brahmans of Europe

and America.” Idealism, no doubt, but it is in this regard for the oppressed

beyond the confines of nation and religion that one can locate the conspicuous

distinctions between Gomes and Vivekananda.

In “Dharma for the State?” - an

article that also appeared in Outlook

India (21 January, 2013) - writer Jyotirmaya Sharma begins by underscoring

the “one phrase [...] that effortlessly invokes the name and memory of

Ramakrishna,” who was Vivekananda’s mentor: “Ramakrishna’s catholicity.” The

article, which is an excerpt from Sharma’s book Cosmic Love and Human Apathy: Swami Vivekananda’s Restatement of

Religion (HarperCollins 2013), charges that “Vivekananda, more than anyone

else, helped construct [...] this carefully edited, censored and wilfully

misleading version of his master’s ‘catholicity’.” Like Gomes, Vivekananda travelled

beyond his homeland in the 19th century. Sharma records how “[i]n

1896, Vivekananda gave two lectures in America and England on Ramakrishna.”

Studying these lectures, Sharma finds “that they are placed entirely in the

context of the glorious spiritual traditions of India as contrasted with the

materialism of the West.” While on the one hand a decided subversion of the

universality espoused by Ramakrishna, the essentialism Sharma infers from

Vivekananda’s lectures may also be seen in Adiga’s aforementioned pronouncement

of an East-West dichotomy founded upon casteist notions of restrictive purity.

Of the lectures, Sharma goes on to

mention that “[t]here are frequent references to Hinduism’s capacity to

withstand external shocks, including the coming of materialism in the guise of

the West and the flashing of the Islamic sword. Despite all this, the national

ideals remained intact because they were Hindu ideals.” What should be

perceived here, then, is not only the conflation of nationalism with Hinduism,

but also the theorising of the religious state as needing to be masculinist in

order to withstand purported threat. Accordingly, it is not only Vivekananda

that Adiga troublingly aligns Gomes with, but also “Tilak and Gokhale” as if

the only way to understand the Goan’s place in the Indian context is by placing

him firmly within the male iconicity of nationalism.

Gomes’s position is much more complex

that the easy binary of bad coloniser versus the suffering colonised that Adiga

seems to have adopted, and it is precisely Gomes’s Christianity that sharply

distinguishes him from the Hindu nationalism of Vivekananda, Tilak, and

Gokhale. As Adiga mentions, Gomes may have worn a dhoti to a reception, and

spoken of the hallowed wisdom of the East, as also of the hypocrisy of Western

civilisation. Even so, this should not be read as representative of Gomes’

overwhelming desire to cast off his European self and wholly embrace Indian

subjectivity. Rather it should be seen as a limited strategy that he, as a

member of the Goan Catholic elite seeking greater autonomy within the

Portuguese empire, was using against recalcitrant Europeans. If there was one

position that the Goan Catholic elite of the 19th century espoused,

it was that they were capable of managing the Estado da Índia Portuguesa without metropolitan oversight because

they were not only heirs of the millenarian Indian civilisation that spun the

Vedas, but were also reprieved by their Christian religion and European

traditions. They were not merely Indians superior to the Europeans; they were

Goans superior to both the Europeans, as well as the subcontinentals because in

either case they had a marker that trumped the other: ancient Indian culture against

the Europeans and Christianity and European culture against the subcontinentals.

Nor was the contest that Gomes was in necessarily a simple case of natives

versus those with foreign blood as Adiga seems to suggest when recounting the

case of Bernado Pires da Silva, who in 1835 was “[t]he first Indian to rule

colonial Goa.” In attempting to craft Goan history within the narrow frames of

nationalist British Indian history, Adiga fails to highlight that the Goan polity

of the time was the scene of a vicious battle for dominance among the local

dominant castes, that included the metropolitan Portuguese, the Luso-descendente

caste, the Catholic Brahmins, the Hindu Brahmins, and the Catholic Chardos

(Kshatriyas), with theatres spread over Goa and the metropole.

Gomes’s position is much more complex

that the easy binary of bad coloniser versus the suffering colonised that Adiga

seems to have adopted, and it is precisely Gomes’s Christianity that sharply

distinguishes him from the Hindu nationalism of Vivekananda, Tilak, and

Gokhale. As Adiga mentions, Gomes may have worn a dhoti to a reception, and

spoken of the hallowed wisdom of the East, as also of the hypocrisy of Western

civilisation. Even so, this should not be read as representative of Gomes’

overwhelming desire to cast off his European self and wholly embrace Indian

subjectivity. Rather it should be seen as a limited strategy that he, as a

member of the Goan Catholic elite seeking greater autonomy within the

Portuguese empire, was using against recalcitrant Europeans. If there was one

position that the Goan Catholic elite of the 19th century espoused,

it was that they were capable of managing the Estado da Índia Portuguesa without metropolitan oversight because

they were not only heirs of the millenarian Indian civilisation that spun the

Vedas, but were also reprieved by their Christian religion and European

traditions. They were not merely Indians superior to the Europeans; they were

Goans superior to both the Europeans, as well as the subcontinentals because in

either case they had a marker that trumped the other: ancient Indian culture against

the Europeans and Christianity and European culture against the subcontinentals.

Nor was the contest that Gomes was in necessarily a simple case of natives

versus those with foreign blood as Adiga seems to suggest when recounting the

case of Bernado Pires da Silva, who in 1835 was “[t]he first Indian to rule

colonial Goa.” In attempting to craft Goan history within the narrow frames of

nationalist British Indian history, Adiga fails to highlight that the Goan polity

of the time was the scene of a vicious battle for dominance among the local

dominant castes, that included the metropolitan Portuguese, the Luso-descendente

caste, the Catholic Brahmins, the Hindu Brahmins, and the Catholic Chardos

(Kshatriyas), with theatres spread over Goa and the metropole.

If Adiga really believes in the

project of securing visibility for those marginal regions and personages that

do not figure in usual conceptions of the Indian cultural and political

landscape, this cannot be achieved without accounting for both the peculiarities

of a location apart from the nation-state and the vexed relationship between

the two. It is not colonisation alone that chronicles a history of the marginalisation

of Goans, but also the contemporary postcolonial condition. Adiga asks if Portuguese,

“the language of the Inquisition” can “be called an Indian language” as it was

one of Gomes’ “mother tongues.” One could put this strange question to Sanskrit,

or indeed any language used by rulers anywhere: can the language of the Manu

Smriti, the language that advocated the horrifying oppression of Dalits, be

called an Indian language? By equating Portuguese language and culture with the

Inquisition alone, Adiga negates the formation and endurance of Portuguese

culture in the former colonies. He brushes aside a whole gamut of cultural

innovations by peoples, many of them subaltern, who still cherish their

traditions, even if he does allude to them in passing.

The memory of the Inquisition, as

Adiga posits it, either shames if one is a Catholic, or it hurts if one

professes Hinduism. This essentialist rationale proceeds to permit Catholics to

feel ashamed and Hindus to feel victimised, thereby leading to the

victimisation of their Other. The majoritarian Hindu politics in Goa with all

its trappings of casteist purity has made sure, quite successfully, with the

insensitive misuse of the history of the Inquisition, as well as conversion,

the perpetual marginalised status of the subaltern Goan Catholic, and those

seldom mentioned groups, like Muslims. Correspondingly, language is another

site of contention. Gomes’ other language, as Adiga indicates, was Konkani.

Adiga rightly offers that Konkani is “now Goa’s official language,” and also

that “Catholics, aware that their presence in Goa is diminishing [...], seek to

protect their heritage.” But what Adiga obscures is that the postcolonial state’s official recognition of Konkani is only in the Devanagri, and not the Roman script largely used by Catholics.

For the Goan in Goa and for the

marginalised elsewhere in the country, it is not useful to simply be squeezed

into a preset notion of Indianness, but for that very category to be critiqued

at every turn for its lack of inclusiveness by design.

(This essay was collectively written with R. Benedito Ferrão, DaleLuis Menezes, and Amita Kanekar

(This essay was collectively written with R. Benedito Ferrão, DaleLuis Menezes, and Amita Kanekar

It was first published in Outlook India.com on 6 Sept 2013.)