On the fifteenth

of this month a number of Goans awarded by the Central Government came out with

a statement wherein they indicated their upset at the spurt in violent attacks

in the country. Subsequently, some of the individual members of this group, and

a few other awardees made independent statements indicating their upset at the

intolerance that was being manifested in the country. All of these Goans

awarded by the Sahitya Akademi made statements indicating that they while they would

have liked to return their awards, they would in fact not do so just yet.

Rather, they would wait to see what the executive committee of the Sahitya

Akademi had to say.

There is

something quite odd about these Goans’ statements. To not actually return an

award, but merely threaten to do so is

frankly quite bizarre. After all, if one wants to return the award, one should

do so. If one is not going to return the award as yet, one should keep quiet

about it, until one actually does so. Contrary to the opinion

of the noted lyricist Gulzar, returning an award is not the only option that litterateurs have to protest. As wielders

of the pen, they can essay articles, issue press statements, script plays of

protest, before they actually get down to returning the symbolic honour that

has been bestowed on them. To threaten to return their awards, therefore, seems

not only presumptuous, but in fact craven.

Rather than

coming across as an act of moral uprightness, the statements of these Nagari

Konkani writers comes across as cowardly. It is as if the Sahitya Akademi award

meant too much to them, such that they could not bear to return it. Some would

argue that this is not the case; that these writers were influenced by the opinion of Amitav Ghosh who argued that one should not disrespect the

institution by returning the award, but take issue with the current leadership

of the Akademi. Hence, the route preferred by our Goans, of waiting till the

Executive Committee of the Akademi made a statement condemning the murder

especially of Prof. Kalbargi.

This is a

plausible explanation. However, if one observes the nature of the relationship

between the Nagari Konkani writers and the Sahitya Akademi as a representative

of the Indian nation, one realises that there was a reason why these writers

would have been susceptible to the Ghosh’s advice in the first place. To

explain this relationship, one must make reference to a statement made by

Pundalik Naik at the Konkani

Rastramanyathay Dis 2008 (Konkani National Recognition Day) organised by

the Goa Konkani Akademi (GKA) on 20 August, 2008. At this event Naik, who was

then President of the GKA indicated that it was only in 1992, when Konkani was

included in the Eighth schedule of the Indian Constitution and recognised as a

national language, and when subsequently Konkani in the Nagari script found

space in the Indian rupee note, that he felt like he had become a full citizen

of the Republic.

This is a

plausible explanation. However, if one observes the nature of the relationship

between the Nagari Konkani writers and the Sahitya Akademi as a representative

of the Indian nation, one realises that there was a reason why these writers

would have been susceptible to the Ghosh’s advice in the first place. To

explain this relationship, one must make reference to a statement made by

Pundalik Naik at the Konkani

Rastramanyathay Dis 2008 (Konkani National Recognition Day) organised by

the Goa Konkani Akademi (GKA) on 20 August, 2008. At this event Naik, who was

then President of the GKA indicated that it was only in 1992, when Konkani was

included in the Eighth schedule of the Indian Constitution and recognised as a

national language, and when subsequently Konkani in the Nagari script found

space in the Indian rupee note, that he felt like he had become a full citizen

of the Republic.

One could

dismiss this statement as mere rhetoric, but looking at Naik at that moment, I

was convinced that it was more than rhetoric. Naik was making an honest

representation of his sensations at the time. It struck me then that the fact

that Naik, possibly representative of many Nagari writers, felt like a full

citizen of India only in 1992, when in fact Goa had been integrated into India

way back in 1961 was indicative of a profound sense of insecurity about one’s

identity of belonging to the Indian nation. Having been thus alerted, I

realised that the history of the interventions of this Nagari writers can be

read as evidence of their insecurity as to whether they belong or not. This

insecurity can explain the vehemence with which many of them have launched

themselves against both Konkani in the Roman script, as well as the demands

that English be recognised as a state-supported medium of instruction. Given

that until 1987 it was Konkani in the Roman script that defined Konkani in Goa,

they were keen that a script that is perceived as foreign by some benighted

Indians not be the mill-stone that prevents them for participating in Indian

nationalism.

This kind of

insecurity is evidenced not only by the Nagari writers, but a variety of others

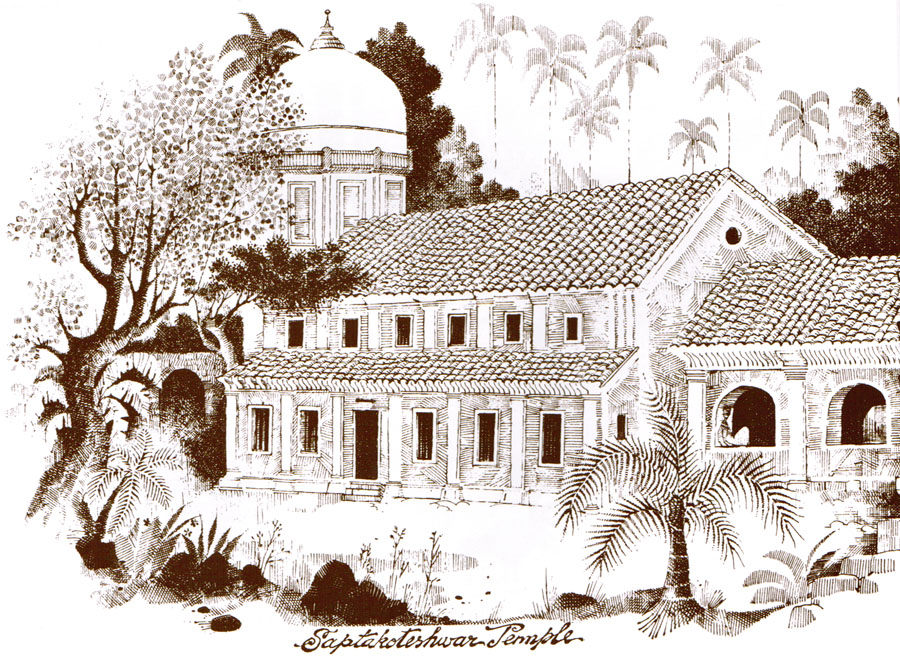

as well. Take the full scale destruction of Goan temples that have taken place

since Goa’s integration into India. Temples in the peculiar Goan style have

made way for structures of dubious aesthetic merit that are seen as more in

keeping with styles that are seen as properly Indian.

A similar anxiety is evidenced among (Indian) nationalistically inclined Catholics as well. They go out of their way to provide Sanskritic names for their children, eschew English, or Portuguese, make a fetish about educating them in Konkani, ask their wives to wear saris.

Given that the

awardees from Goa were among the only group in the country to threaten to

return their awards, one can suggest that there is some unique about the Goan

condition that allowed for this situation. I would argue that these writers

were loath to return these awards because they are insecure about their Indian

identity, and see these awards are assurances that the Indian nation recognises

them as one of their own. If this is true, then the situation is highly

unfortunate and merely a statement of the impossibility of the Goan ever being fully Indian.

Given that the

awardees from Goa were among the only group in the country to threaten to

return their awards, one can suggest that there is some unique about the Goan

condition that allowed for this situation. I would argue that these writers

were loath to return these awards because they are insecure about their Indian

identity, and see these awards are assurances that the Indian nation recognises

them as one of their own. If this is true, then the situation is highly

unfortunate and merely a statement of the impossibility of the Goan ever being fully Indian.

(A version of this post was first published in the O Heraldo on 30 Oct 2015)